Section 01: Monopolies

Monopolies are on the other end of the continuum from pure competition. A monopoly consists of one firm that produces a unique product or service with no close substitutes. Entry into the market is blocked, which gives the firm market power (i.e., the power to raise price above marginal cost). Historically, pure monopolies are rare and often short lived because the reason for their existence (usually blocked entry) is somehow weakened. For example, patents expire, new resources are often discovered, and new technologies allow new competitors into the market. We will expand on these sources of monopoly power later. It will also become clear that firms have an incentive to try to gain a monopoly. Studying the attributes and behavior of a monopoly is a useful reference point particularly when looking at the other market structures.

As an interesting side note, when there is only one seller in a market, it is called a monopoly, but when there is only one buyer in the market, it is called a monopsony. We will save our discussion on monopsonies until near the end of the course.

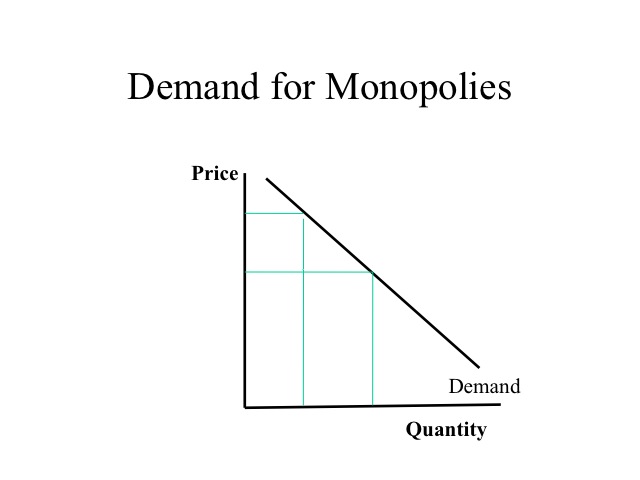

A monopoly determines not only the quantity to produce but also the price it will charge. The demand curve the firm faces is the market demand curve. Thus if it wants to sell more, it must lower the price. Does a monopoly have an incentive to advertise? Since the firm is also the market demand curve, it has one hundred percent of the market share; however, monopolies may advertise to increase overall market demand or to improve goodwill or public relations.

Recall from our discussion of perfect competition that when firms are able to obtain economic profits, other firms/entrepreneurs are attracted to the industry and entry will occur until economic profits are reduced to zero. But if there is a barrier, entry by profit-seeking firms does not happen and economic profits can persist. There are a variety of different barriers that may allow a firm to exercise market power (which really just means that a firm can set price above marginal cost and extract positive profits). Barriers to entry include the following five barriers.

1. Legal Barriers

Some of the most obvious legal barriers are patents, copyrights, and licenses. Patents reward firms for investing millions of dollars in research and development of new products. They give a company the sole right to produce the product for a limited time period in order to help it recoup the research and development costs. Examples of patents include a pharmaceutical company’s exclusive right to sell a medication or a chemical company having exclusive rights to sell a chemical it has developed. Firms will often use those profits to research and develop new products. Similar to patents, copyrights grant exclusive rights for products developed by firms such as films or books. Finally, licenses granted by the government restrict the number of firms in an industry. For example, some metropolitan areas, such as New York City, require taxi cabs to purchase a medallion, which are limited in number. In 2009, the price of these medallions exceeded $750,000. Other examples of licenses include states that limit the number of liquor licenses or cities that limit the number of cable companies.

Governments often control essential services in a city such as water, sewer, and garbage. If all households are required to have garbage service and the government grants the contract to one firm, that firm would have a monopoly.

Reference:

http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/travel/2009-08-05-taxi-cab-new-york-city-medallions_N.htm

2. Control of Necessary Inputs

Another barrier to entry can occur when firms are able to own or control the necessary inputs or resources, and as a result, they may be able to control the market. In the early 1900’s, Standard Oil’s control of the oil refining and transportation was partly responsible for the passage of antitrust legislation which specifies regulations regarding monopolies and monopolizing practices. In the 1940s the government accused Aluminum Co. of America of being a monopoly by controlling the mineral bauxite, an essential input for making aluminum. De Beers’ control of rough diamonds allowed it to control and set diamond prices.

References:

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,764369,00.html

http://www.forbes.com/2000/08/31/shilling_index.html

3. Network Externalities

Network externalities may also create barriers to entry. A positive network externality occurs when the value of having or using an item increases as others use the item. A phone or fax machine, for example, becomes more useful when others have phones or fax machines. If the market is dominated by a particular product or brand, e.g., a computer operating system or certain software, a network externality exists so users don’t want to change products or brands. So the externality creates a barrier for other firms to enter with a competing product.

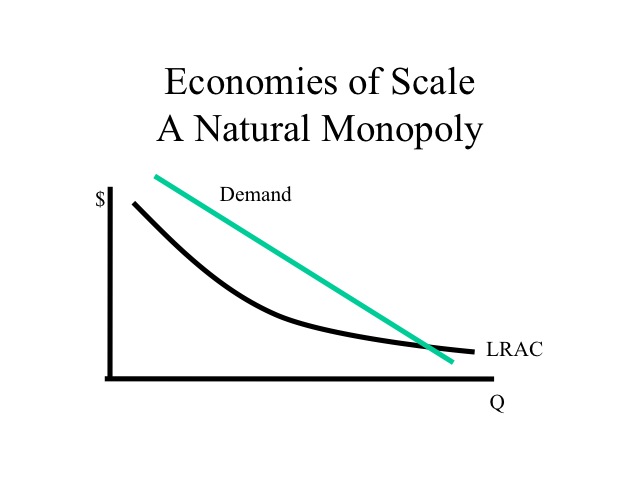

4. Economies of Scale

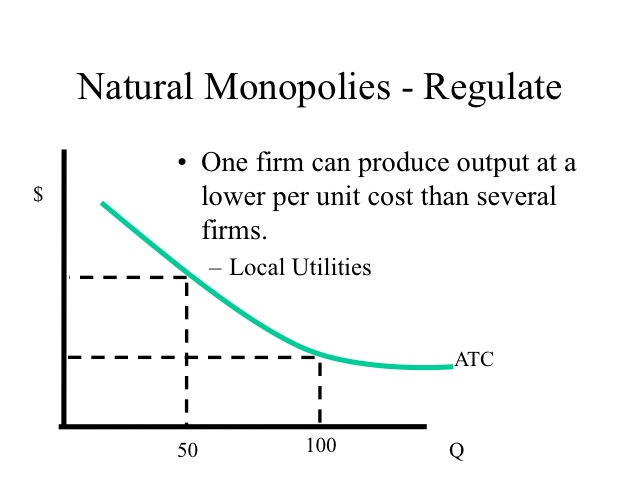

In certain industries natural monopolies exist where the long run average cost curve continues to decline in the relative region of demand. Consequently, one firm is able to produce enough for the market at a lower per unit cost than would be the case if two firms shared the market. In this case, positive profits can exist, but entrants cannot enter to capture some of these profits because sharing the market means they have to enter at a smaller scale of operation and thus face higher average costs. The transmission of electricity is an example of a natural monopoly.

5. Strategic Behavior

Firms may undertake other strategic actions to discourage potential competitors from entering the market through pricing or production decisions. For example, a small town may have only one gas station that sets prices a little lower than the monopoly price (i.e., it does not act as a pure monopolist) in order to keep profits low enough to deter others from entering the market. Alternatively, a firm may build a facility larger than needed as a threat that it will increase production if other firms attempt to enter the market. These strategic actions create a barrier to entry.

While not a true monopoly, Toy’s ‘R’ Us faced antitrust concerns for allegedly threatening that it would not sell manufacturers’ goods unless they fixed the price of those goods when sold to competing discount stores.

Reference:

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125573656435491057.html

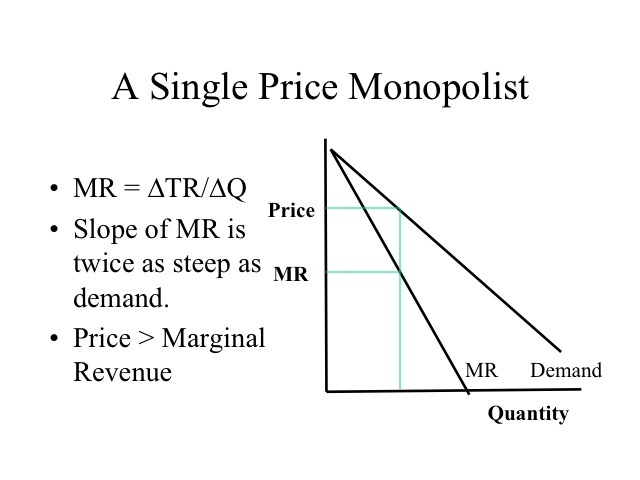

Unlike firms in pure competition that only decide the quantity to produce, monopolists must determine both the quantity and price. But these are not independent choices. Because a monopolist faces a downward sloping demand curve, she must lower the price if she wants to sell more goods (recall that the law of demand states that this inverse relationship exists between price and quantity demanded). Given that the monopolist must charge the same price to all consumers (i.e. she cannot price discriminate), then to sell more, she must charge a lower price, not only on the last good she wants to sell, but on all of the product that she could have sold at the higher price. This has important implications for marginal revenue. It means that marginal revenue falls at twice the rate of the demand curve (i.e. the slope is twice as steep). This might best be seen with an example. Let’s assume that a monopolist can sell 1 barrel of oil for $80 or 2 barrels for $79 each. To sell two barrels, price must drop by $1. But MR for the second one is change in TR divided by change in quantity or (158 – 80) / (2-1) = $78. So MR fell by $2 ($80-78) – twice the rate as price!!

The marginal revenue curve for a single priced monopolist will always be twice as steep as the demand curve. Since the demand curve reflects the price and the marginal revenue curve is below the demand curve, the price is no longer equal to the marginal revenue as it was in pure competition.

The extra mile for the mathematically inclined students:

For those wanting to see mathematically why the marginal revenue curve is twice as steep as the demand curve, here is the math. Let’s assume Demand is P = 10-2Q. In our example, the slope of the demand curve is -2. Total Revenue which is equal to price times quantity equals (10-2Q)Q = 10Q-2Q2. Using this equation we can evaluate the change in total revenue as Q changes. For example, let’s look at the change in total revenue as quantity changes from 3 to 4. When Q equals 3, the total revenue is 4 and when Q equals 4, the total revenue is 8. A change in total revenue of 4 dollars as Q increases by one implies a slope of -4 which is twice the slope of demand. For those who have had calculus, take the first derivative of 10Q-2Q2 to get the marginal revenue of 10 – 4Q, which gives a slope of -4.

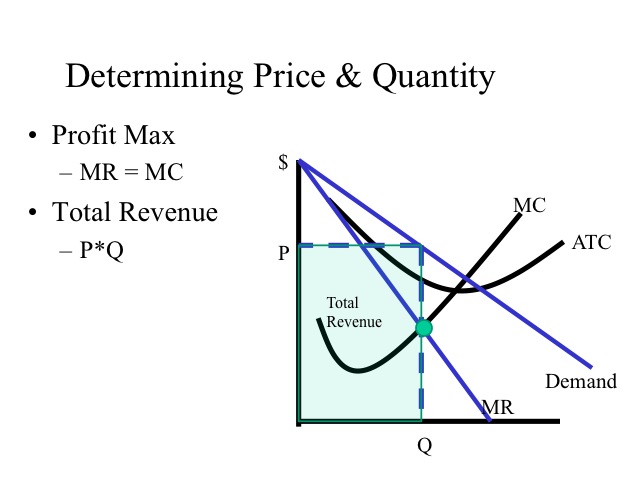

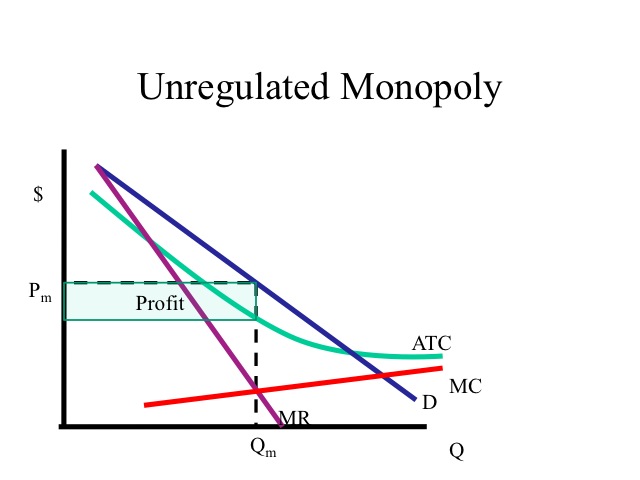

Determining Price and Quantity

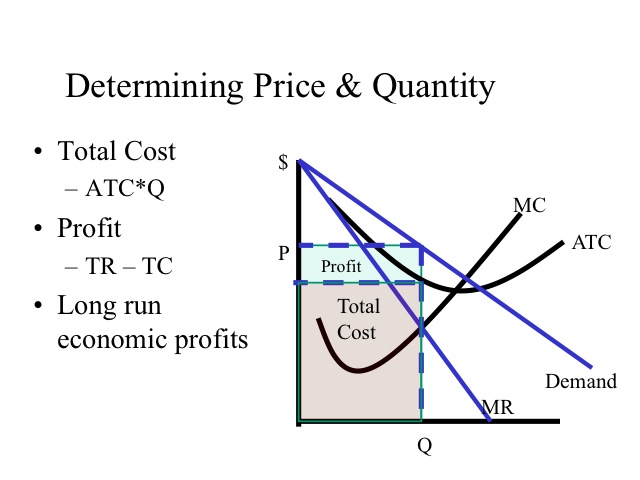

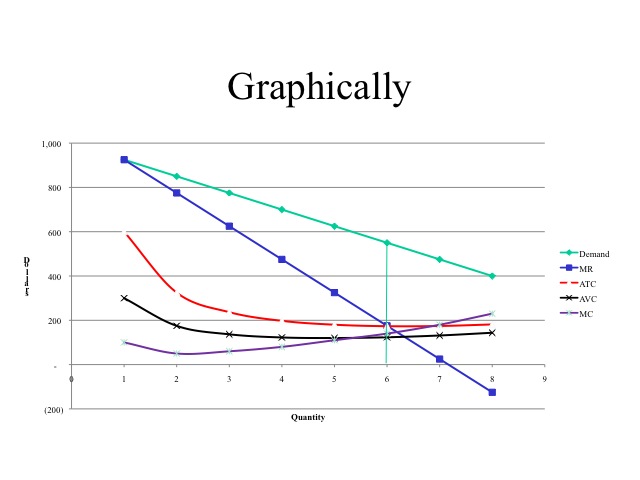

Profit maximization for a monopoly charging a single price will occur where marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. It is important to note that this gives the profit maximizing quantity but the price is determined by going up to the demand curve. That is, the price is obtained based upon what consumers are willing to pay for that quantity level which is determined by the demand curve.

Profits for the monopolist are obtained by calculating total revenue (TR) minus total cost (TC). TR=optimal price * optimal quantity (the combined area of the blue and grey boxes in the figure). Taking the average total cost times the profit maximizing quantity gives the total cost. In the short run, a monopoly may earn short run profits or losses, but unlike firms in pure competition that have zero economic profits in the long run, monopolies can maintain long run profits. If long run profits are negative, the firm would leave the industry and the good would no longer be produced, since the monopoly was the only firm in the industry.

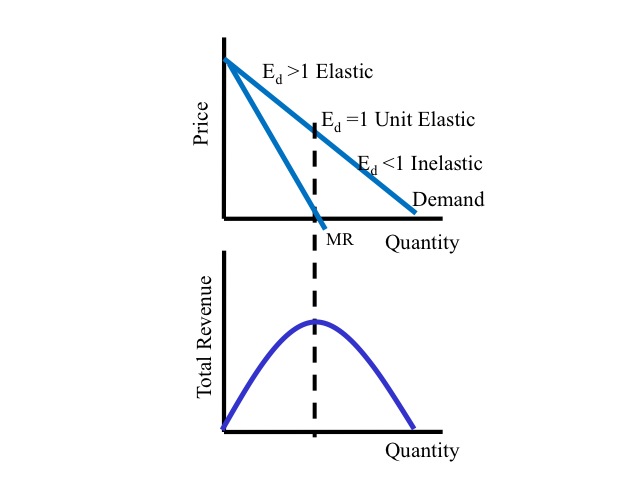

Recall from our discussion on elasticities that along a linear demand curve, there is an elastic and inelastic portion. In the elastic portion, lower prices increases total revenue, and in the inelastic portion total revenue falls as price decreases. Total revenue is maximized at unit elasticity which occurs where marginal revenue is zero.

This provides for an important observation. Because we would expect marginal cost to be positive and a monopolist chooses to produce where MR=MC, we can conclude that a monopolist would only produce in the elastic region of the demand curve.

Practice

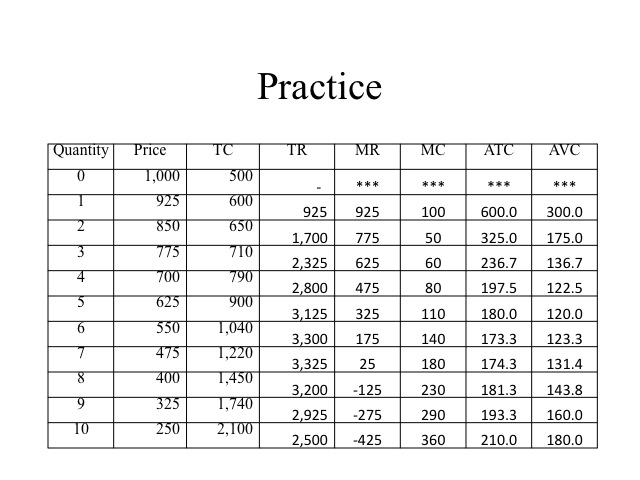

1. Determine the profit maximizing quantity and price for a single priced monopolist. Is the monopolist producing in the elastic region of the demand curve at that point?

Answer

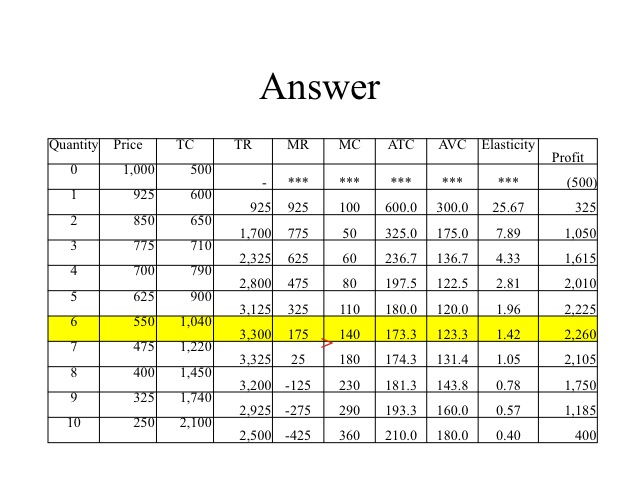

Following the decision rule of producing where the marginal revenue equals the marginal cost, we can determine that producing six units and charging a price of $550 will maximize profits. At the sixth unit, our marginal revenue is 175 and the marginal cost is 140. At seven units the marginal cost would exceed the marginal revenue. In looking at the column on the far right, we verify that this is the quantity that maximizes profits. At six units of output, the mid-point elasticity between five and six units is 1.42, which is elastic.

At six units the marginal revenue is still greater than the marginal cost, but since it is less at the seventh unit six units maximizes profits.

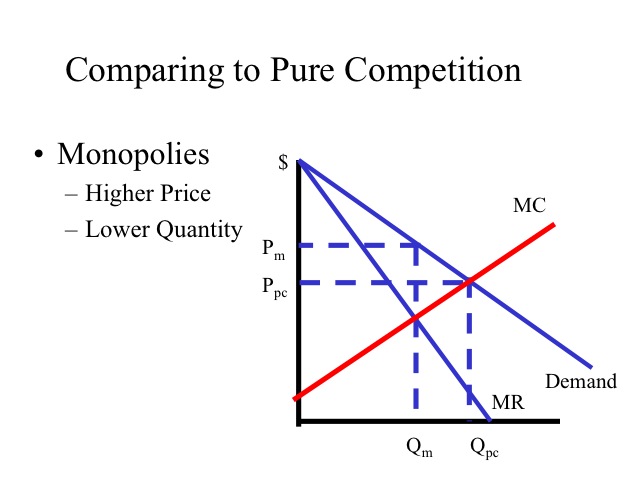

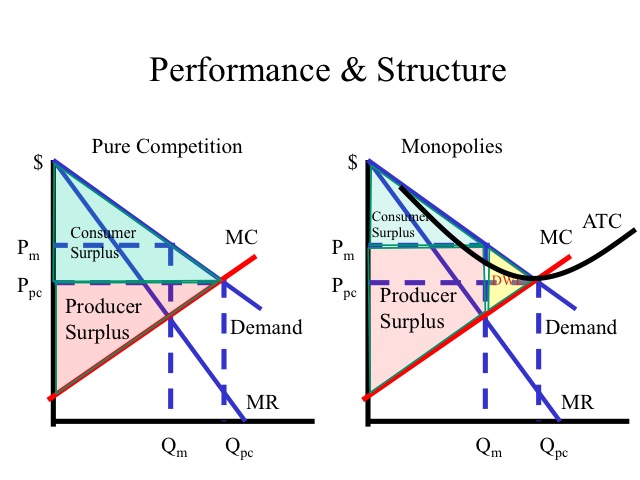

Recall that purely competitive firms produce where MC is equal to price and that industry supply is obtained by horizontally adding the MC curves of the firms in an industry. In equilibrium, the industry supply curve (the sum of the MC curves) crosses the demand curve. If the monopoly was to act in the same fashion, it would produce where its MC curve crosses the demand curve (just like the sum of the MC curves cross the demand curve in pure competition – only it is the sum of one curve). So in comparing the outcome for pure competition to that of monopoly we see that a single price monopolist will produce less than the purely competitive market and charge and higher price.

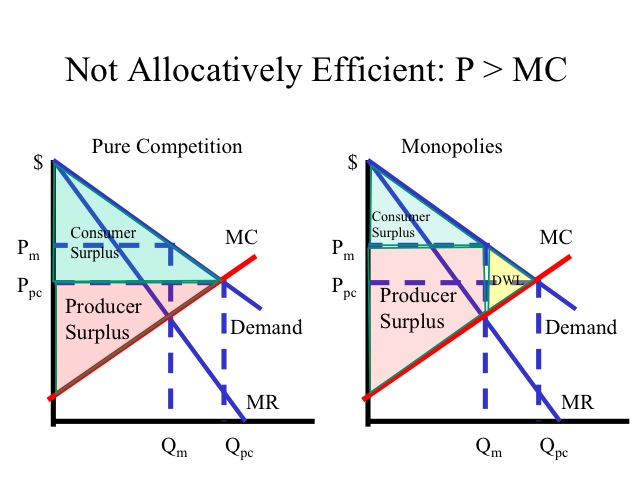

In pure competition, economic surplus which is consumer plus producer surplus, is maximized. The industry is allocatively efficient producing where the price is equal to the marginal cost. By restricting output and raising price, the single price monopolist captures a portion of the consumer surplus. Since output is restricted, a portion of both the consumer and producer surplus is lost. This loss of economic surplus is known as deadweight loss, that neither the consumer nor the producer enjoy.

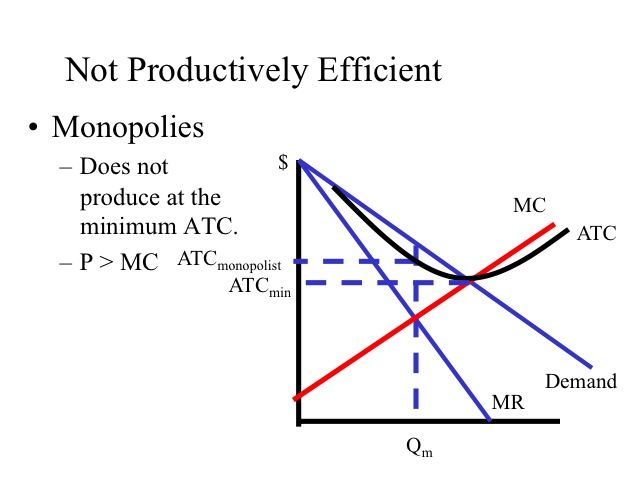

A monopolist may or may not be productively efficient; it depends on whether it is producing at a point where ATC is at the minimum point. Productive efficiency means least-cost and this occurs where ATC is at its minimum point. In general, monopolies are not productively efficient. Monopolies may also suffer from what is called x-inefficiency. X-inefficiency arises when costs creep up due to lack of competition and/or actions pursued by the monopolist to protect its monopoly position. These monopoly protecting actions are also called rent-seeking activities.

Monopolies will often pursue rent seeking activities spending time or money on activities that are not related to the production of the good or service but intended to increase the market power and profitability of the firm. For example, major soft drink companies, such as Coke or Pepsi, will offer millions to a university or stadium if they are allowed to be the sole soft drink vendor. Likewise athletic wear firms may offer a university payments or discounts if they are allowed to be the sole vendor of apparel. These expenditures are not related to the production of the good or service but give them a monopoly in the respective markets.

Legal cartel theory suggests that some industries may seek to be regulated or desire that regulation continues, so that the number of firms is limited and the existing firms can act like a monopoly. Regulation such as limiting the number of firms or individuals in a market (e.g., medical school, state liquor licenses, or taxi cabs in New York City) may be done with “good intentions,” but they grant existing firms more market power which leads to higher prices and a lower quantity supplied.

Section 02: Price Discrimination

Price Discrimination

If instead of charging each consumer the same price, a firm could price discriminate, which means charging different prices to different consumers based upon their willingness to pay, how would they behave? What would be required for a firm to be able to price discriminate?

Certain conditions must hold in order for a firm to charge different prices for the same product. First, a firm must be able to set the price (i.e. it must have some market power). Second, the firm must be able to segment the market into groups based upon either their willingness to pay or their different elasticities of demand. Third, the firm must be able to prevent resale of the item from one market segment to another.

These may seem like difficult or unlikely conditions. But in fact, price discrimination can be found in a variety of sectors including automobile sales, movie and airline tickets, utilities and phone rates. Even student discounts are a form of price discrimination.

First Degree or Perfect Price Discrimination

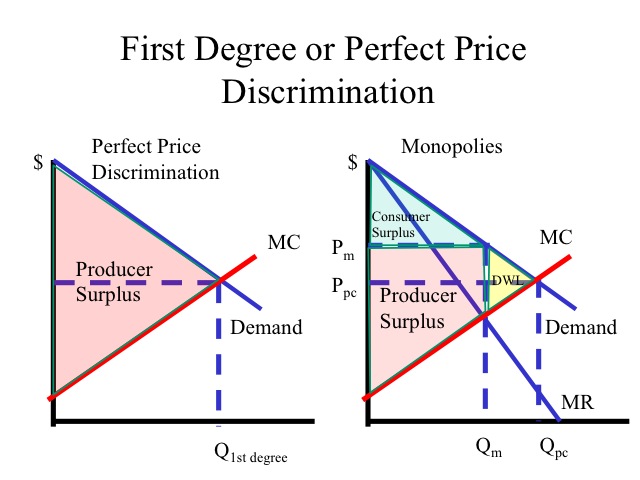

There are three different degrees or levels of price discrimination. These levels are related to how well the monopolist can identify individual willingness to pay and segment the market accordingly. First degree or perfect price discrimination is when a firm charges each consumer their maximum willingness to pay, which is reflected by the demand curve. As in other cases, it is optimal for the firm to choose its output at the point where MR=MC. But if a firm can charge each person his/her maximum willingness to pay, then MR = price as found on the demand curve. So it would be willing to sell its products up to the point where the MC curve crosses the demand curve, i.e. where MC = price = MR. This means that not only will the firm would be willing to sell more units than it did as a single priced monopolist, but it will also be allocatively efficient because price equals marginal cost at the last unit. However, each consumer is now paying her maximum willingness to pay, and therefore receives no consumer surplus. So although the output level is allocatively efficient and the same as perfect competition would obtain, the distribution of economic surplus is quite different – the firm extracts all of the surplus!

Since a firm may be unable to assess each consumers maximum willingness-to-pay and the cost of gathering that information may be prohibitive, first degree price discrimination is often difficult /impossible to implement. The law profession is perhaps the best example of perfect price discrimination – their offer for a “free consultation” is designed to obtain information on willingness and ability to pay. Some other examples of attempts at perfect price discrimination would be a car salesman who tries to assess each consumer’s maximum willingness-to-pay and charges accordingly. Auctions also try to reach each consumer’s maximum price.

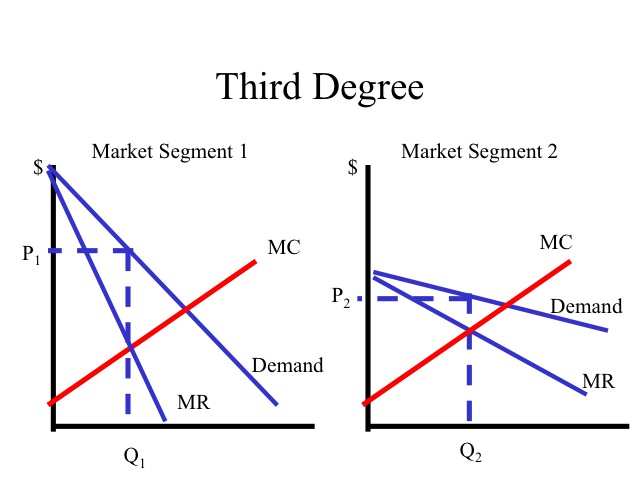

Third Degree Price Discrimination

When a monopolist cannot perfectly identify and segment consumers based upon individual willingness to pay, there still may be a way to extract some (but less) consumer surplus to increase profits. Second degree price discrimination (to be discussed later) and third degree price discrimination might be employed under the right conditions. Third degree price discrimination may be employed when the firm cannot identify individual demands, but can identify groups of consumers that have similar demands and can segment them based upon some easily identifiable characteristic such as age, time of purchase, residency, or location. Then the monopolist charges different prices to the different groups based on their relative elasticities of demand. The more inelastic the demand, the higher the price. This type of price discrimination is most common. Being able to segment the market, into groups that have different elasticities, allows the firm to charge different prices and increase overall profitability. Recall that the firm must be able to prevent the resale of the good for price discrimination to work. This is why we often see third degree price discrimination in the service sector, where the nature of the product or service makes the resale of the good to another segment of the market difficult or impossible. Here are a few examples of third degree price discrimination.

Movie theaters often charge different prices based on the time of consumption and age. The elasticity of demand for those attending a matinee is more elastic than those during primetime, so a lower price is charged for the matinee. Young children and senior citizens have different elasticities of demand than young adults, which allow the theaters to price accordingly.

Airlines also price discriminate. Those purchasing tickets at least two weeks in advance typically get a lower price than individuals purchasing tickets only a day or two before the flight. The distance and destination of the flight also make a difference since there are fewer substitutes if one is flying to say Hawaii verses another city within the state.

Gas stations within the same city often price discriminate charging a higher price at stations located close to the interstate or on the main roads.

Some theme parks, such as Disneyland and Disney World, offer residents of California and Florida different prices than non-state residents.

Second Degree Price Discrimination

Second degree price discrimination is implemented when the monopolist knows that there are two or more groups of consumers with different willingness to pay, but she cannot identify which consumers belong to each group. If we make things simple and assume that there are two groups, a high demand group (H) and a low demand group (L), then ideally, she’d like to charge a high price to the H group and a low price to the L group. But if the she does this, consumers in the H group will claim to be from the L group and everyone will get the low price. Second degree price discrimination or block pricing charges different prices to different consumer groups based on the quantity consumed. That is, the firm knows that the H consumers are willing to purchase a higher quantity than the L consumers at the same price. Therefore, it will set a price for the L group that extracts all of their consumer surplus for a small quantity level (say $2 for a package of 4 rolls of toilet paper), but this would leave H consumers with some consumer surplus because they have a higher demand. To get at least some of that consumer surplus from them, the monopolist sets a higher price for a larger package that targets H consumers (say $3.50 for a package of 8 rolls of toilet paper). The volume discount encourages the H consumers to buy the larger package and also allows the firm to extract more of their consumer surplus, because they get them to buy a larger quantity (otherwise they would only buy the 4 roll package). Unlike perfect price discrimination that extracts all of the consumer surplus, in second degree price discrimination, the high demand group still keeps some.

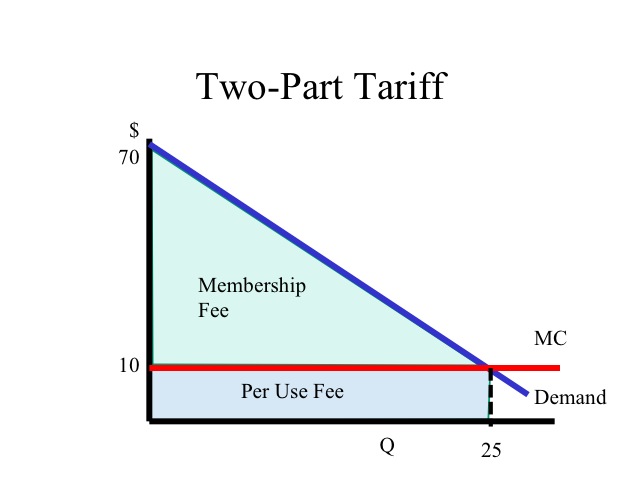

There are a number of pricing strategies that do not seem like price discrimination, but in fact are! One is worthy of note: the two-part tariff. The two-part tariff charges individuals an upfront membership fee then also charges them a per use fee. Under the right conditions, the two-part tariff makes perfect price discrimination possible. For example, some golf courses and health clubs charge an annual membership fee in addition to the per use fee for each round of golf or workout. If the marginal cost of providing a round of golf is ten dollars, then the golf club charges a ten dollar per use fee and the golfer decides to play 25 rounds of golf per year. If there was no membership fee the area below the demand curve and above the price would be consumer surplus, however, by charging a membership fee equal to the area of consumer surplus (recall the area of a triangle is .5*base*height or .5*25*60 = $750), the golf club is able to convert the consumer surplus into additional revenue for the firm. This is of course, first degree or perfect price discrimination if the membership fee differs by consumer based upon willingness to pay. Alternatively, if the firm can’t identify individual demands, but knows the demands for different groups, it could still use two-part tariffs to obtain the second degree price discrimination outcome. Either way, the firm extracts some of the consumer surplus as additional profits.

Another example of a two-part tariff would be a cell phone company that charges a monthly fee in addition to a per minute charge. Although other pricing strategies exist, you should be able to understand the incentive for why firms would want to price discriminate.

Section 03: Antitrust and Regulation

Performance and Structure

Monopolies and firms that collude to act like monopolies, reduce competition and create inefficiencies in the market. We have seen that single priced monopolists are neither allocatively efficient (price equals marginal cost at the last unit produced) nor productively efficient (producing at the lowest average cost). Consequently, the United States government has passed certain laws that restrict monopolies.

Government can evaluate a market based on the structure of the market, i.e., the number of firms in the industry and the barriers to entry, or by the market’s performance or conduct, i.e., the behavior of the firms and the resulting prices and efficiencies. Should a monopoly exist, the government can pursue a variety of options:

(1) break up the monopoly under antitrust laws;

(2) regulate the monopoly; or

(3) ignore the monopoly, if they anticipate that the monopoly will be short lived or have negligible impact.

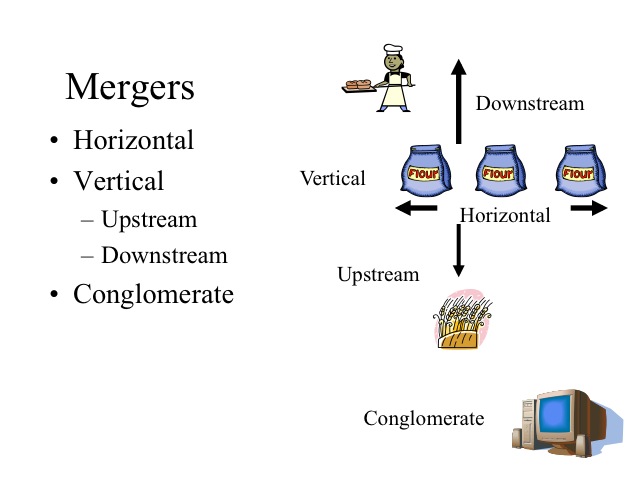

Whenever firms become large in size or large relative to their industry, policy-makers recognize that these firms are more able to pursue monopoly-type conduct and obtain inefficient market outcomes. At the same time, growth of a firm, as we have seen, allows it to capture economies of scale and scope. So when large firms merge, the benefits have to be measured against the potential for efficiency losses. There are three basic types of mergers. A horizontal merger is the merger or consolidation of two or more producers of the same product or service. For example, if a flour mill buys another flour mill. Vertical mergers occur when firms at different stages of production of a product merge. For example, a flour mill that buys a wheat farm would be an example of an upstream vertical merger (upstream means input-supplying), while the flour mill buying a bakery would be an example of a downstream vertical merger (downstream means output-using). Conglomerate mergers occur when the merging firms produce unrelated products, such as a flour mill purchasing a computer company. Conglomerate mergers may allow a firm economies of scope or to diversify. Historically, several tobacco companies have purchased food companies, such as Kraft, to help them diversify and improve their public image.

In 1890, the Sherman Antitrust Act was passed to reduce the power of firms that controlled a large percentage of a market. It made it illegal to participate in activities in that result in the “restraint [of] trade or commerce”, such as price fixing, and activities which monopolize or attempt to monopolize. This legislation targeted firms such as the Standard Oil Company which was monopolizing the refining and distribution of the petroleum. However, this powerful law was vague in many respects and subsequent laws were passed to more explicitly outline activities that were illegal.

The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, empowered the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to prevent or stop unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts in or affecting commerce. Today the FTC and the Department of Justice’s antitrust division have the responsibility to investigate firms for antitrust behavior.

The Clayton Act of 1914, strengthened the Sherman Antitrust Act, making illegal price discrimination of “commodities of like grade and quality” when it is reduces competition and is not justified by cost differences. The purchase of a competitor’s stock and having interlocking directories, where the individuals are serving on both board of directors, are also illegal if they reduce competition. The Clayton Act also prohibits tie-in sales, where the purchase of one product is a condition of sale for another product. Later, the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950 closed loopholes in the Clayton Act by restricting companies from the purchase of the physical assets of competitors. While horizontal mergers were scrutinized under the Sherman Antitrust Act, vertical and conglomerate mergers could be blocked under the Celler-Kefauver Act if they could reduced competition.

References:

http://www.stolaf.edu/people/becker/antitrust/statutes/clayton.html

http://www.stolaf.edu/people/becker/antitrust/statutes/ftc.html

If an industry has a natural monopoly, a single firm is able to produce at a lower per unit cost compared to having multiple firms in the industry. Thus, governments typically opt to regulate instead of breaking up natural monopolies. An electrical generating company, for example has high fixed costs and the marginal cost of running power to one more house is very low.

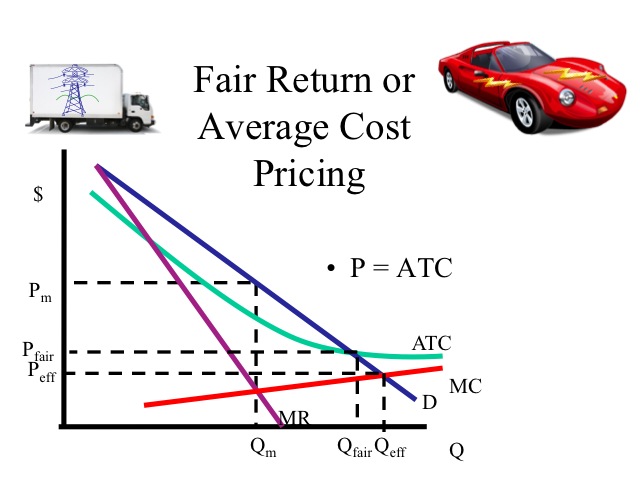

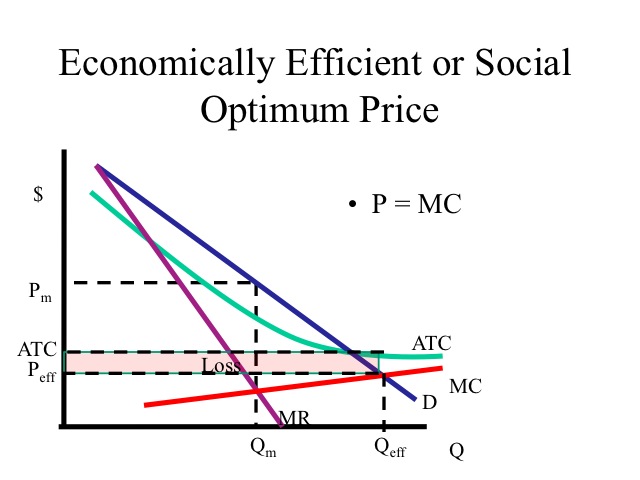

An unregulated single-priced monopoly would maximize profits where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, producing Qm and charging price, Pm. As the government steps in to regulate a market, what price should they allow a monopolist to charge?

Economically Efficient or Social Optimum Price

The economically efficient or social optimum price would occur where price equals marginal cost, making the industry allocatively efficient. However, since the average total cost is declining in the region of demand, and marginal cost intersects average cost at the minimum, marginal cost will be below the average cost in the relevant range of demand. If regulators force a monopoly to price at this point, where price equals marginal cost, they would force the monopoly to incur a loss or negative economic profits, which would eventually force the monopoly out of business. Since the monopoly is the only producer, government could subsidize the monopoly for these losses such that they earn a normal return, but this is often politically difficult.

Fair Return or Average Cost Pricing

Alternatively the government could force the monopoly to produce where price equals average total cost, leaving the firm a zero economic profit. Thus the firm will remain in the industry since it is covering all opportunity costs. As demonstrated in our graph, the price is less than that of the unregulated monopoly but higher than the economically efficient price. The drawback of this policy is that firms have no incentive to control costs. If costs rise, they can simply petition the government for price increases. But if the firm improves productivity and pursues cost cutting measures, the government would force them to lower prices. Thus local utility companies may have newer equipment and vehicles simply due to this perverse incentive.