The United States and the Global Economy

Section 01: Specialization and Trading

Absolute Advantage

Adam Smith taught the importance of specialization and trade when he taught: “It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what will cost him more to make than to buy. The taylor does not attempt to make his own shoes, but buys them of the shoemaker.”

An individual or country has an absolute advantage in the production of a good when it can produce the good using fewer resources compared to another. For example, a student may be great at both sports and academics—this would give him an absolute advantage over those students who are great at academics but not at sports, or who are great at sports but not at academics. It costs him less (effort, time, etc.) to produce the same results as it costs other students to produce those same results. Similarly, a country may have an absolute advantage in both banana and soybean production, which would mean that it’s more efficient at producing these than other countries, which may be great at either banana production or soybean production, or at neither.

The Advantages of Specialization and Trading

If an individual or country has an absolute advantage in many things, would there still be benefit to specializing and trading?

To answer this question, let’s use the example of a deserted island with only two inhabitants: Robinson Crusoe and Friday.

Assume that their diet will consist of fish and coconuts, and that Robinson can catch 4 fish per hour or gather 6 coconuts per hour, while Friday can catch 3 fish per hour or gather 2 coconuts per hour. Note that Robinson has an absolute advantage in both fishing and coconut gathering. If each person wants 6 fish and 6 coconuts per day, would there be an advantage in them specializing and trading?

If they don’t specialize, who long will it take each person working alone to meet their daily needs? Robinson would spend an hour and a half fishing and one hour gathering coconuts, for a total of 2.5 hours. Friday will spend 2 hours fishing and 3 hours gathering coconuts, for a total of 5 hours.

If specialization takes place, it should be in the area where the individual or country has what is known as a comparative advantage—that is, where the marginal opportunity cost of producing a good is lower relative to the other individual or country. Recall that

If Robinson spent an hour fishing instead of gathering coconuts, he would have to give up 6 coconuts to get 4 fish, so his marginal opportunity cost would be

= 1.5 coconuts per fish

If, instead, he spent an hour gathering coconuts, he would give up 4 fish and gain 6 coconuts. Robinson’s marginal opportunity cost would then be

= 0.66 fish per coconut

Friday’s marginal opportunity cost of spending an hour fishing instead of gathering coconuts would be 2 coconuts for 3 fish, or two-thirds of a coconut per fish.

= 0.66 coconut per fish

His marginal opportunity cost per additional fish would be

= 1.5 fish per coconut

To see advantages to specializing and trading, we now look at the marginal opportunity costs of each. We find that the marginal opportunity cost per additional fish is less for Friday compared to Robinson. Friday gives up only 2/3 of a coconut per additional fish, compared to Robinson’s 1.5 coconuts per additional fish. Since Friday has a lower marginal opportunity cost for fishing, he is said to have a comparative advantage in fishing. In comparing the marginal opportunity cost for gathering coconuts, we find that Friday’s is 1.5 fish per coconut, while Robinson’s is only 2/3 of a fish per coconut. Thus, Robinson has a comparative advantage in coconut-gathering, while Friday has a comparative advantage in fishing.

Is it advantageous for Robinson Crusoe to specialize in gathering coconuts, even though he can do both fishing and gathering better than Friday? If they each specialize, what will be the time savings to each?

If Robinson specializes in gathering coconuts and he must now gather 12 coconuts (6 for himself and 6 for Friday), he would need to work 2 hours. Friday, specializing in fish, would need to spend 4 hours to gather enough fish for both himself and Robinson. Even though he has an absolute advantage, Robinson is able to save half an hour by specializing and trading. Friday is able to save an hour of time by specializing and trading. Even though Friday gains more than Robinson from specializing, each person is better off.

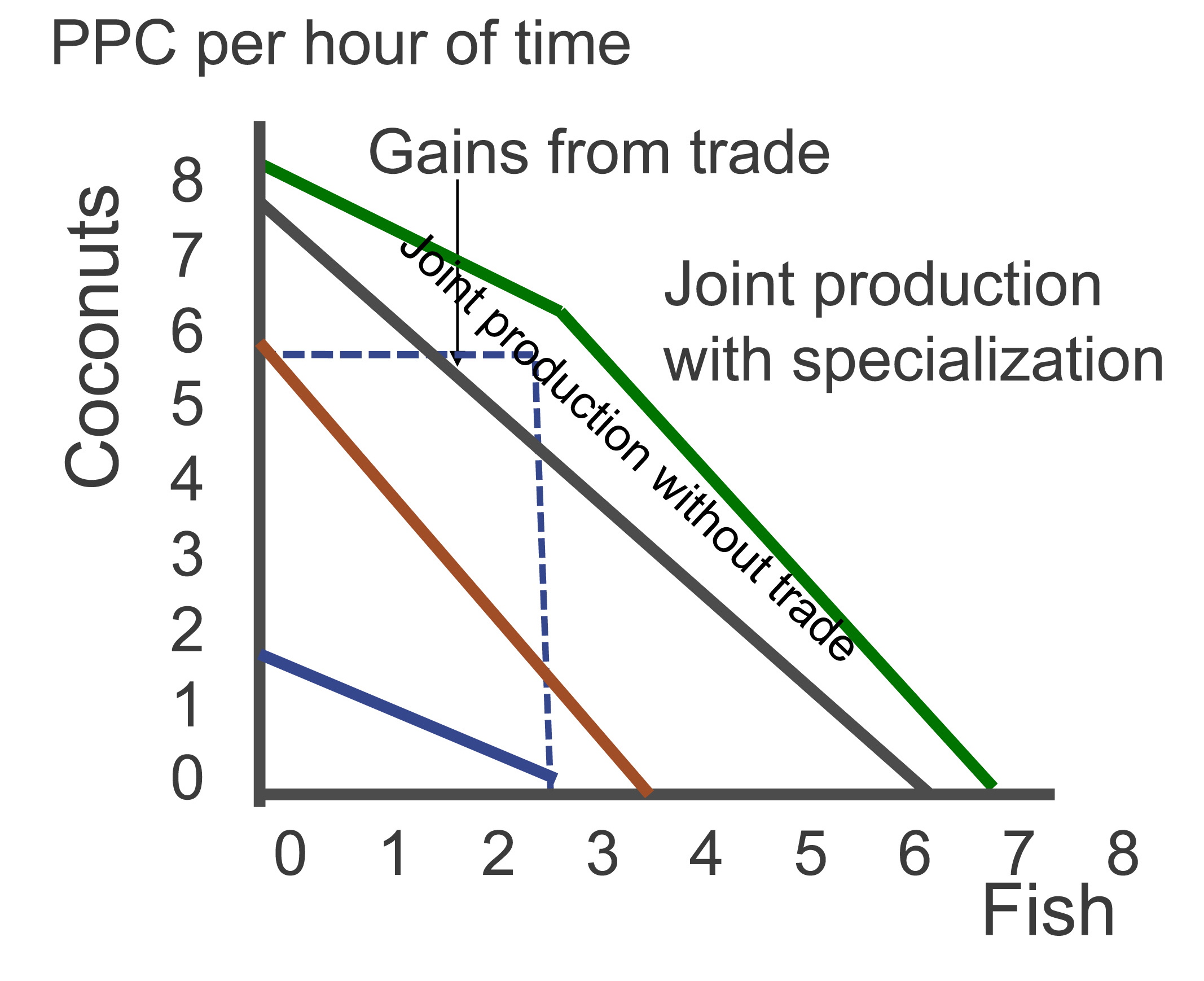

Friday’s output per hour is shown by the PPC closest to the origin. He can gather 3 fish per hour or 2 coconuts per hour. Robinson’s PPC is greater than Friday’s, since he has an absolute advantage in producing both goods. If they don’t specialize, their joint production without specializing is represented by the PPC furthest from the origin.

Specialization allows the joint PPC to shift out even further. If they only produced fish, they could still produce 7 fish per hour, and both gathering coconuts would allow them to gather 8 per hour. By Robinson specializing in coconuts and Friday in fish, they could have 3 coconuts and 6 fish by each working an hour. The outward shift shows the gains from specializing and trading.

Terms of Trade

For trade to take place, each individual must benefit. An individual would not be willing to trade for a good that would cost him more than he or she could make alone. Highest and lowest rate at which the goods would trade for are determined by each individual’s marginal opportunity cost. In our example, Friday is specializing in fish production and Robinson in gathering coconuts. Since they each want some of both, the terms of trade would have to be acceptable to both. In looking at the marginal opportunity costs, we see that the terms of trade range from 2/3 to 1.5. Friday must receive at least 2/3 of a coconut for each fish he gives up, and Robinson would not be willing to pay more than 1.5 coconuts for each fish he receives. Somewhere between this range, both individuals would benefit.

As President Faust points out, we live in an age of specialization wherein it is essential to obtain a good education with the needed technical skills:

We live in an age of specialization. When I was a boy, many people had Model T Fords. Compared to modern cars, they were relatively simple mechanically. Many people were able to fix their own cars by grinding the valves, changing the rings on the pistons, putting in new brake bands, and using a generous supply of baling wire. Nowadays automobiles are so sophisticated that the average person knows very little about how to repair them. The mechanics of today use a computer to diagnose engine problems. I mention this example to encourage you young men to get training and education in order to keep up. Technical education is very important, and the same thing is true in fields of higher education. Any kind of skill requires specialized learning.

— Pres. Faust. “Message to My Grandsons.” Sat. Priesthood Session. April 2007 General Conference.

Section 02: International Trade

As Adam Smith points out, “What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scare be folly in that of a great kingdom. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.”

Since the resources of each country vary, there is a benefit to specializing in a good in which we have a comparative advantage. Although we may have the resources to grow bananas in Idaho, we do not have a comparative advantage in banana production. Thus, we specialize in potatoes and other goods and services in which we have a comparative advantage, and trade for bananas and other tropical fruits from countries that have a comparative advantage in producing those goods.

Foreign Exchange

Although we trade extensively with other countries, we don’t trade a good for a good. Rather, we purchase the goods that we want by paying them with their currency. Other countries, in turn, purchase our goods with our currency. To purchase goods from Brazil, we would have to have the Brazilian currency, the Real. The market for the trading of currencies is the foreign exchange market. The exchange rate, or rate at which one currency will trade for another, is based on the supply and demand of the currencies in that market.

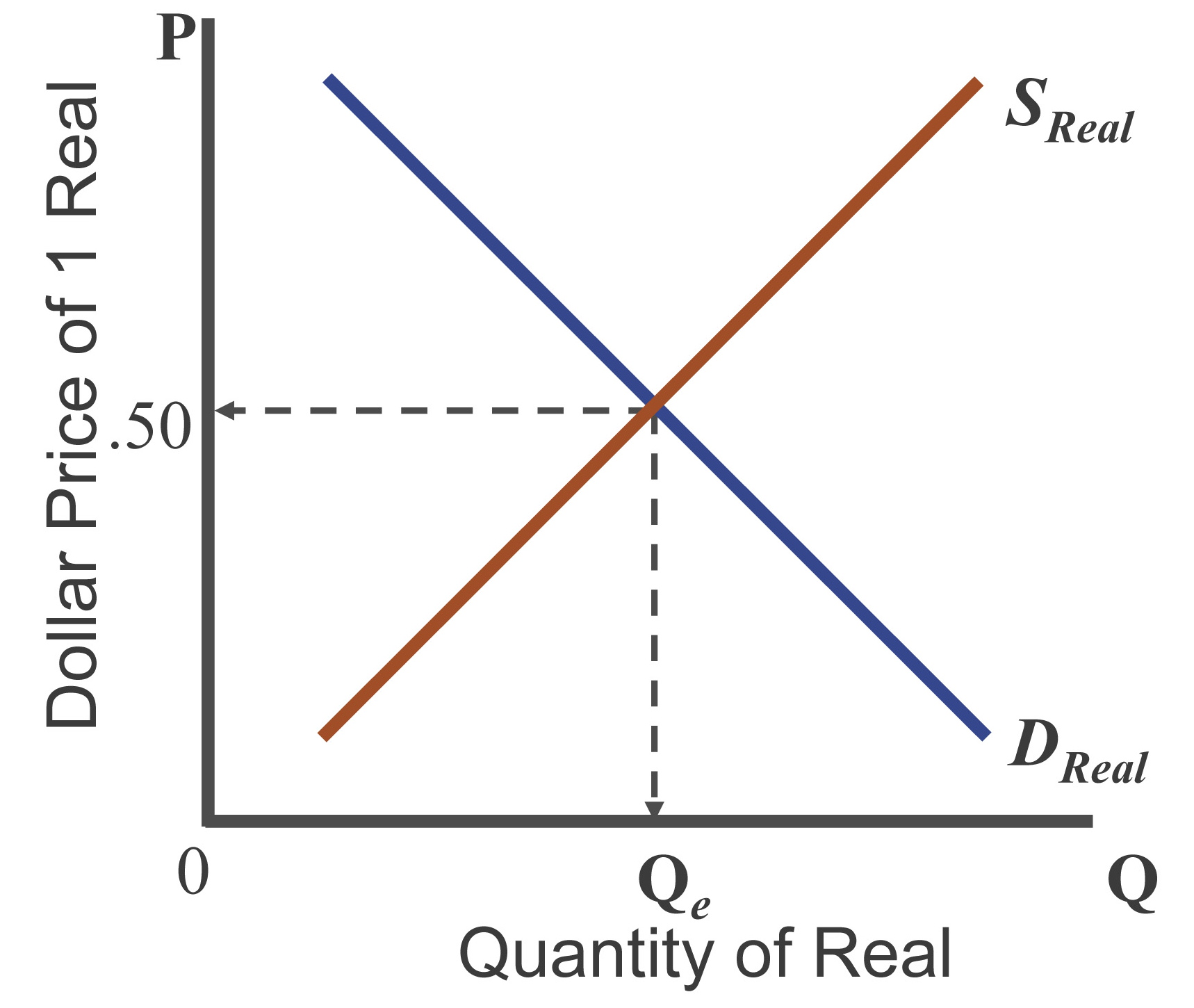

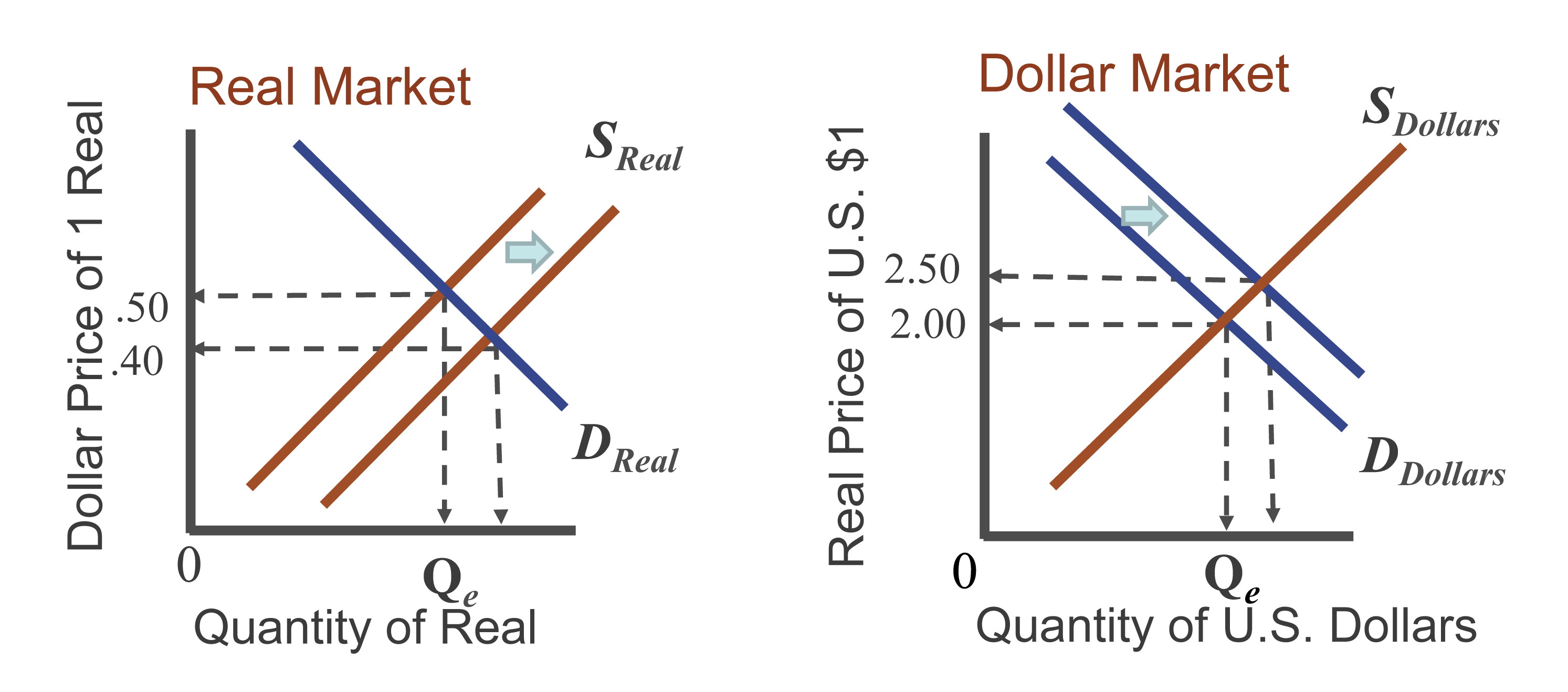

If we simplified the world and looked only at trade between the United States and Brazil, we see that Brazil would demand Dollars to purchase US goods, and as they demand Dollars they are offering Reais in exchange. The United States, wanting Brazilian goods, demands Reais and is offering Dollars in exchange. If the exchange rate were one Dollar for two Reais, then the price of one Real would be 50 cents.

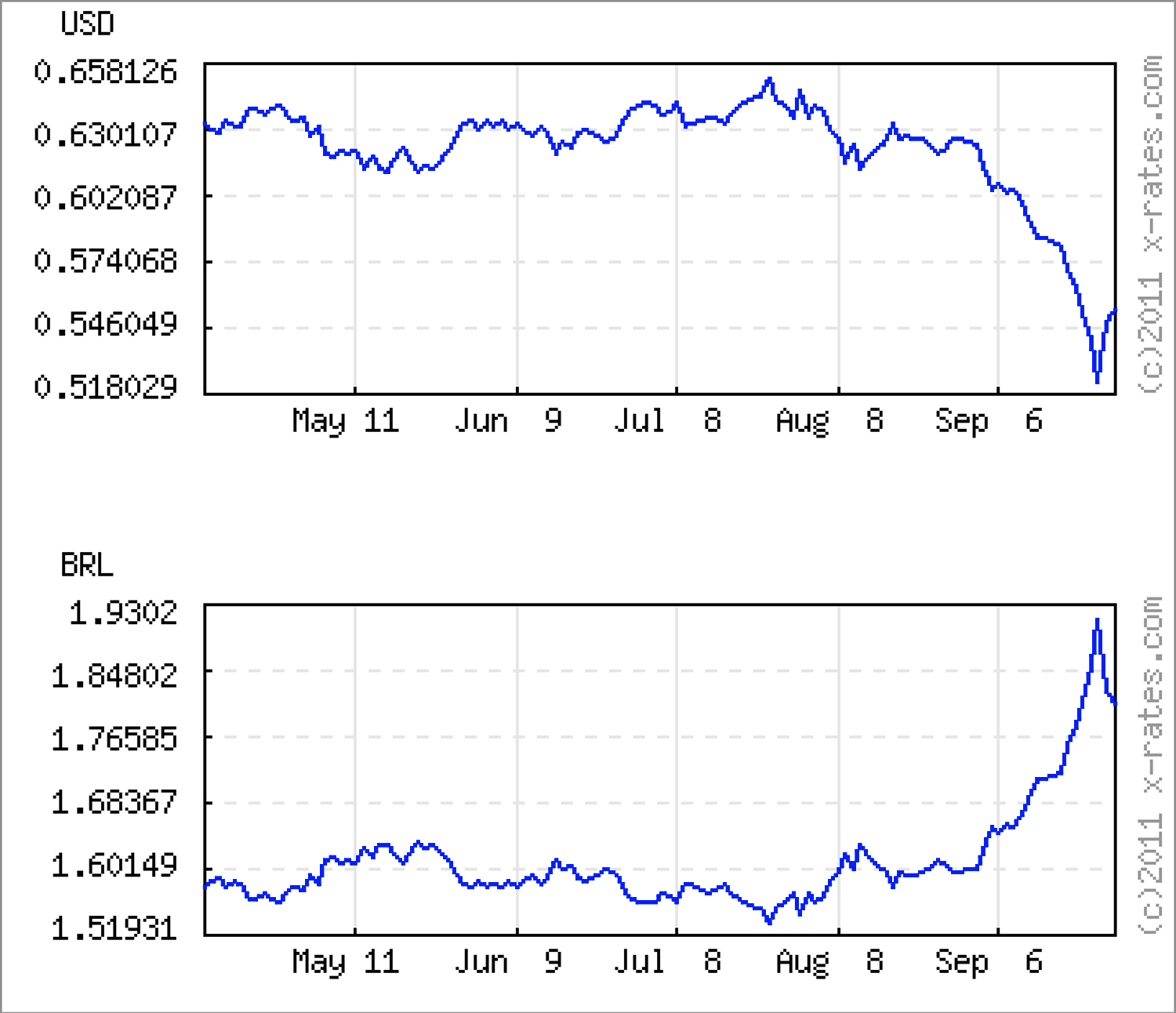

The increased demand for Reais and increased supply of Dollars would change the equilibrium exchange rate. The new equilibrium exchange rate would now be 1 Dollar for 1.5 Real, or $0.67 per Real. The Dollar has depreciated, or weakened, meaning that the Dollar no longer buys as many Reals as before. On the other hand, the Brazilian Real has appreciated, or gotten stronger, since it no longer takes as many Reais to buy a Dollar as it once did.

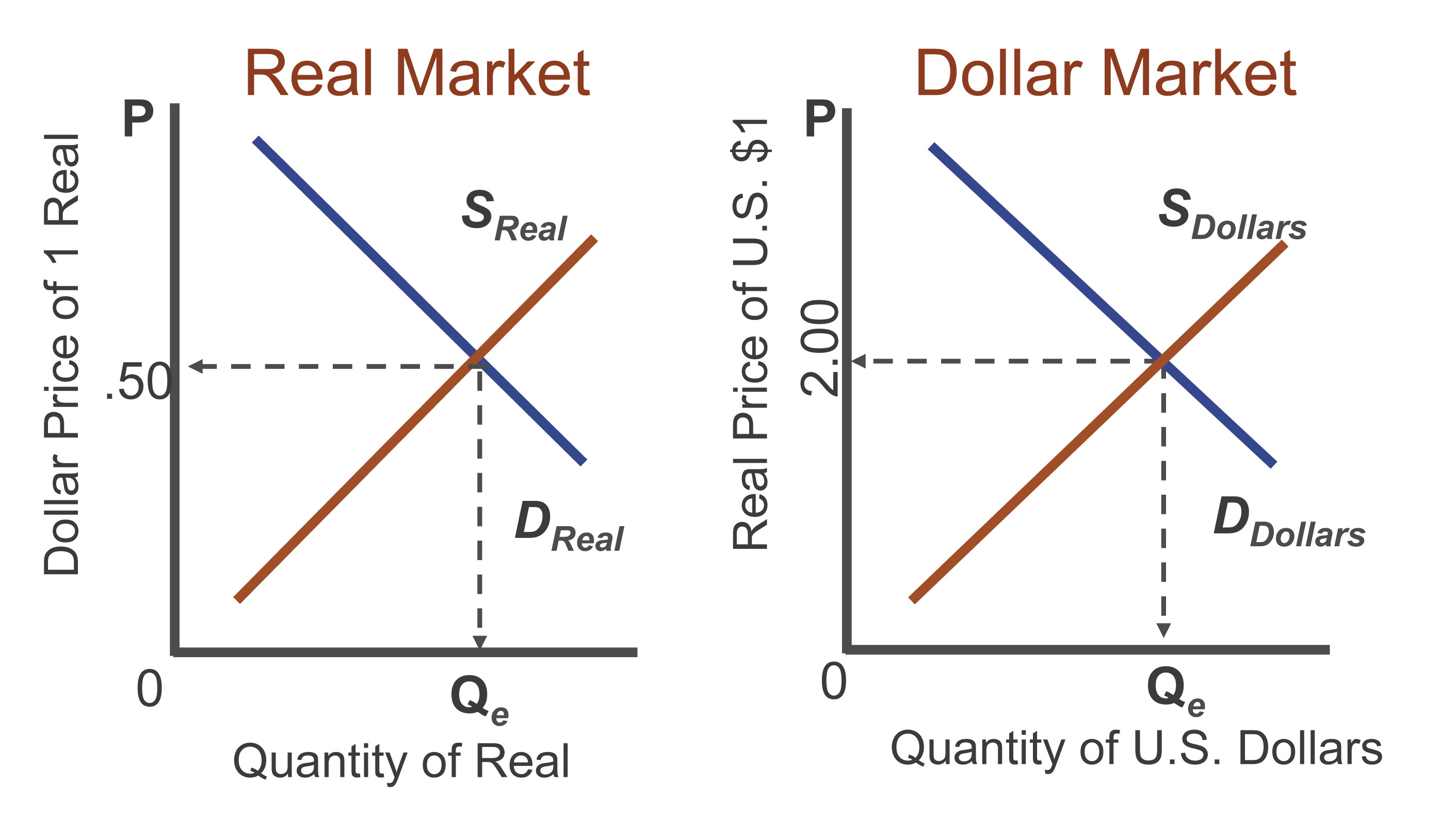

When comparing the currencies of two countries, the supply of one currency equals the demand for another currency. In order to demand one currency, you must supply another currency. The equilibrium is where the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded.

What would happen in the foreign exchange market if the United States wanted more Brazilian oranges? The United States would demand more Reais to pay for the oranges and would supply more Dollars.

Thus, the two markets are mirror images of each other; if the Dollar weakens, the Real strengthens.

What would happen if the US interest rates increased? Brazilians now wanting to take advantage of the higher interest rates on their savings would want to put more money in the United States.

To get the relatively higher interest rates in the United States, Brazilians need Dollars. Thus, the demand for Dollars would increase and the supply of Reals would increase. As a result, the Dollar would now buy more Reais, and it would take more Reais to buy a Dollar. The Dollar has appreciated, and the Real has depreciated.

Flexible Exchange Rates

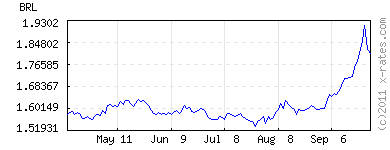

Exchange rates that are determined by the market are known as floating or flexible exchange rates. They fluctuate according to the supply and demand of the currencies.

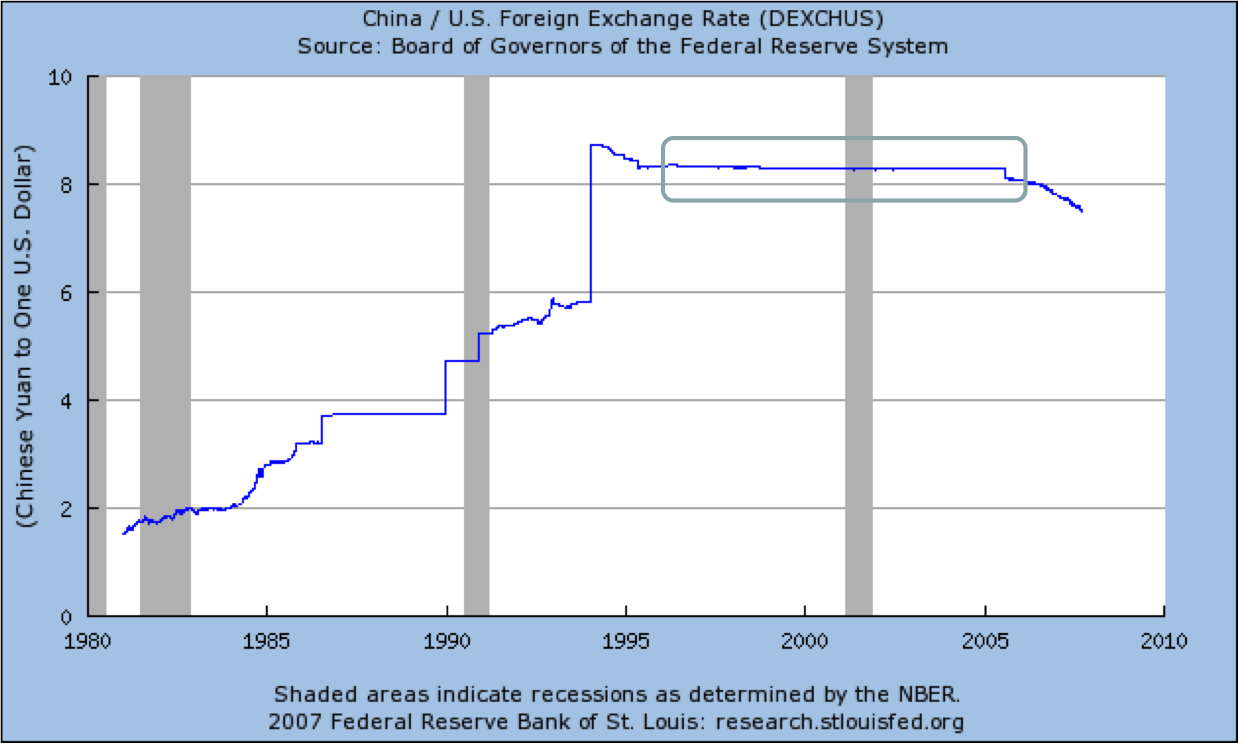

Fixed Exchange Rates

Fixed exchange rates are when a country will specify an exchange rate for the currencies rather than allow the currencies to fluctuate. As shown in the graph below, China fixed an exchange rate between the Dollar and the yuan for a period of time prior to 2005. To maintain the exchange rate, governments must actively buy or sell currencies to keep the desired rate.

What Will It Cost?

The cost of a foreign good or service can be determined once the exchange rate is known. If the exchange rate between the Brazilian Real and the US Dollar is 2 Reais per Dollar, then a trip up the Amazon that costs 600 Reais would cost 300 Dollars.

Exchange Rate Determinants

While many factors influence the exchange rates, the general determinants are the changes in tastes, relative incomes and prices, real interest rates, and speculation.

- Tastes

- Popularity of German cars increases

- Relative Incomes and Prices

- A recession in Japan reduces demand for US goods

- Inflation in Brazil

- Real Interest Rates

- Higher interest rates in United States attracts foreign currency

- Speculation

A Strong Dollar:

A strong Dollar benefits US consumers, since we are able to purchase foreign goods cheaper and travel abroad at a lower cost. Foreign purchases for goods or resources are also less expensive. As a result, we enjoy a lower cost of living since our dollar buys more. The drawback to a strong Dollar is that US goods become relatively more expensive; thus, foreigners will purchase fewer goods from the United States and may decide to travel elsewhere. Imports will rise as we purchase more from other countries, but exports will fall. As a result, there will be less economic activity in the United States. The opposite happens under a weak Dollar: foreign goods cost more, so consumers will purchase more US goods, creating more economic activity in our country.

Section 03: Measuring Trade

Exports are the goods and services produced in one nation and sold to another. Imports are the goods and services purchased by a nation that were produced by another country. If the value of the imports is greater than the exports, the country is said to have a trade deficit. A trade surplus, on the other hand, is when the value of the exports exceeds that of the imports.

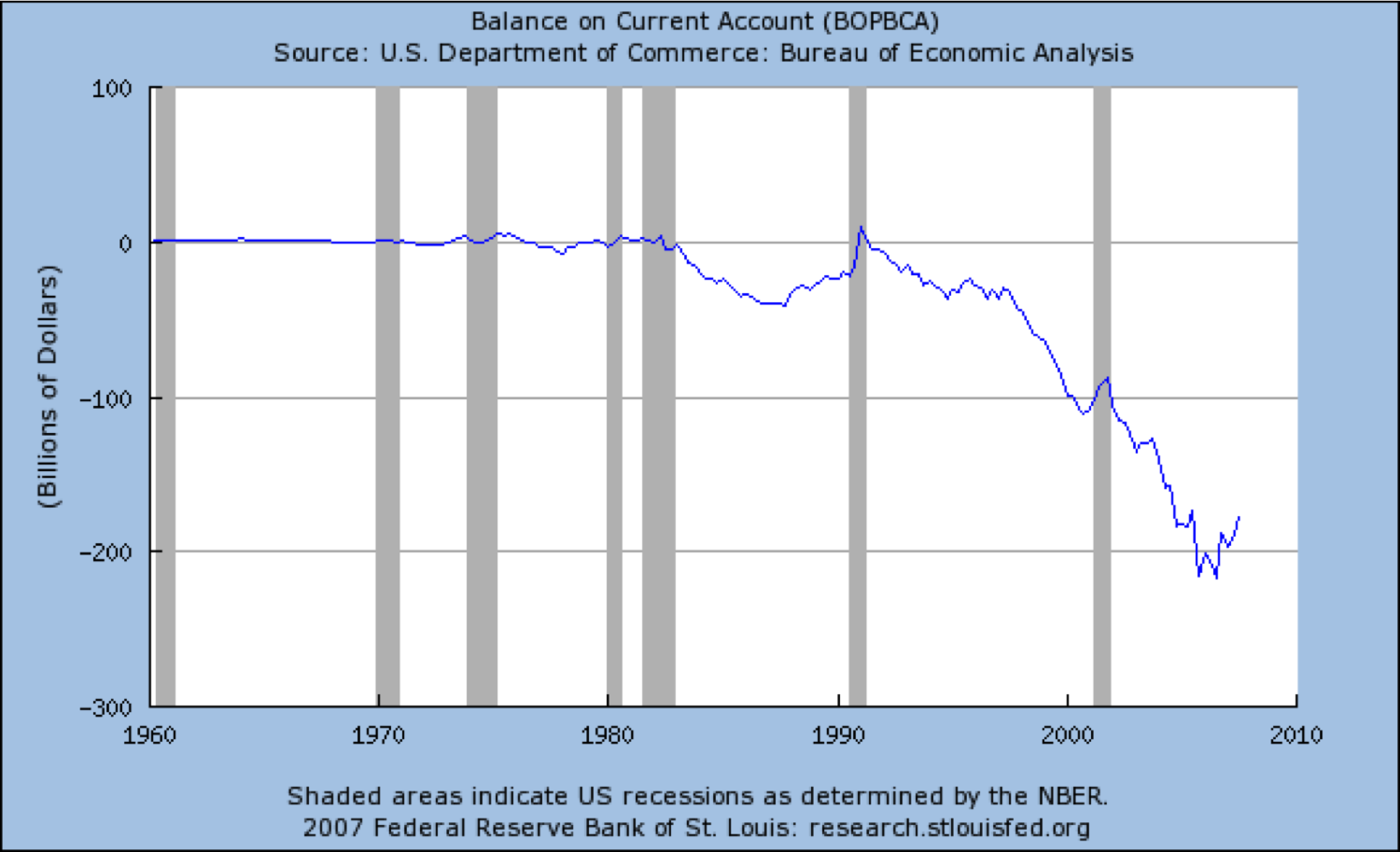

The balance of payments measures the value of goods and services exchanges between two countries. The main categories are the current account and the capital account. The current account measures the value of goods and services exported and imported along the other international transfers of income, including foreign aid, interest, and dividends received from and paid to foreign countries. The capital account measures the long-term income flows, such as the purchase or sale of assets and securities between the countries.

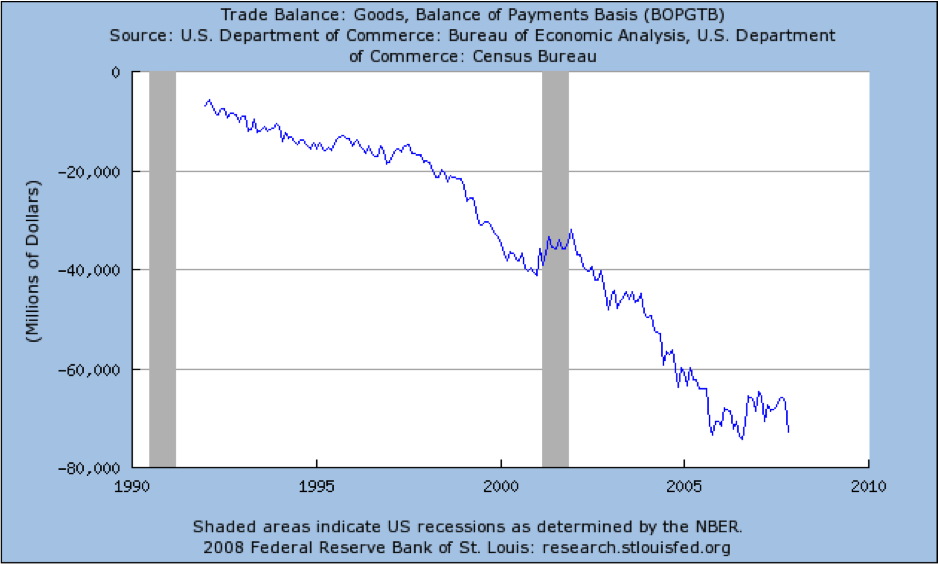

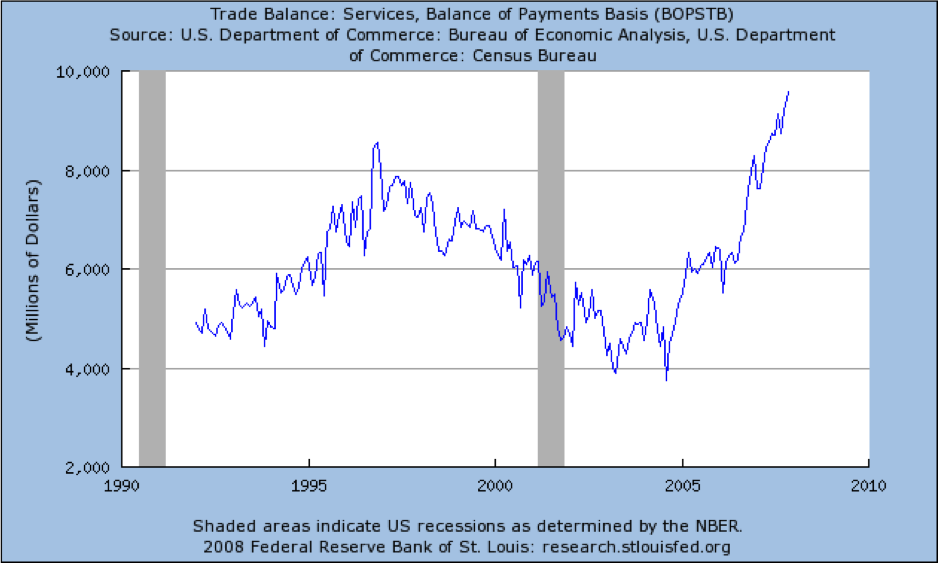

As a nation, we have been negative in the current account for some time.

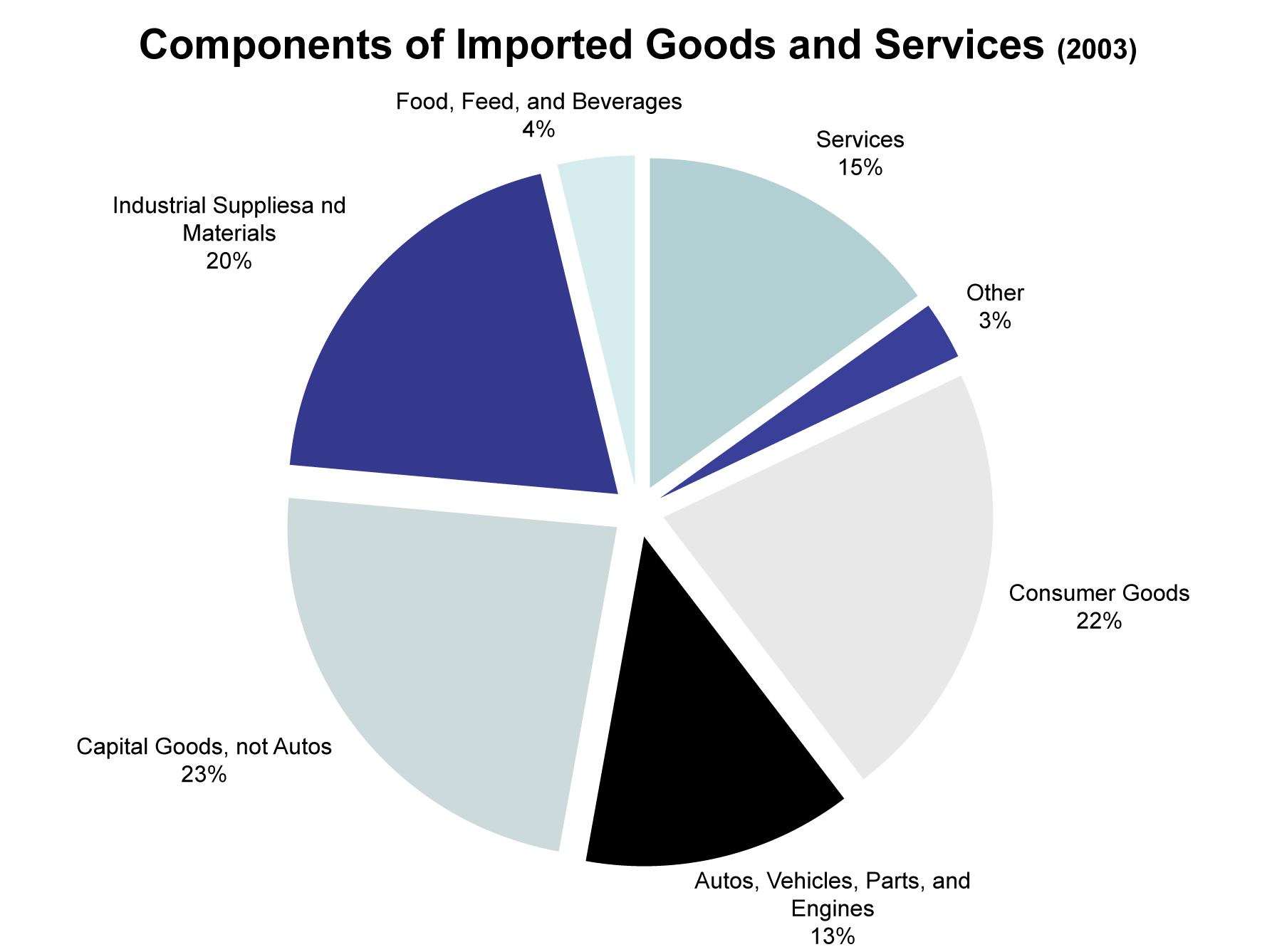

Although we have maintained a trade surplus in services—which would include banking, tourism, transportation, education, and entertainment—we have purchased far more foreign goods, leading to a negative trade balance (see below).

Arguments to Restrict Trade

When free and open trade exists, countries will specialize in the production of those goods and services in which they have a comparative advantage. However, some countries may restrict trade based on the nation's interest. Some arguments for restricting trade include: national security interest; environmental, health, and safety concerns; protection of infant industries; and protection against unfair practices.

Even though a rogue nation may have a comparative advantage in missile production, we may want to continue to produce our own missiles, so we are not dependent on them in the event that they attack us. If another nation produces products that may be harmful to our citizens, such as with lead paint, we may want to restrict trade in the name of safety to our citizens. Infant industries are those that are just getting started and may not be able to compete globally with other, well-established firms. And last, if other countries allow for unfair business practices, such as dumping, or selling the product below cost, the government may choose to step in.

Trade Protection

The typical ways a government will step in to restrict trade include imposing a tariff, a quota, or a non-tariff barrier. A tariff is a tax on an imported good. By making the cost of imported goods relatively more expensive, consumers are more likely to purchase the domestic good. A quota sets a limit on the number of goods that can be imported into a country. Requiring special licensing to certain paperwork would be examples of non-tariff barriers.

Although the good may not face a tax as in a tariff, by raising the cost of importing a good into the country, the government is able to restrict trade. Each of these trade restrictions will create inefficiencies in the market. However, a nation must decide if the loss of efficiency and the resulting higher costs are worth it.

Trade Restrictions

Trade restrictions have long been a source of contention between countries. In 1930, in the midst of a severe recession, government passed the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 to protect domestic producers from foreign imports. However, the policy failed to help domestic producers, since other countries retaliated by placing tariffs on US goods. While imports fell, exports fell even more sharply, pushing the United States deeper into depression.

As a result of the Smoot-Hawley Act,

- Average tariffs increased to 53% on dutiable imports.

- US imports from Europe declined from a 1929 high of $1,334 million to just $390 million in 1932 (decline of $944 million).

- US exports to Europe fell from $2,341 million in 1929 to $784 million in 1932 (decline of $1,557 million).

- Overall, world trade declined by some 66% between 1929 and 1934.

- All of these results of the Act contributed to the Great Depression.[1]

Trade Liberalization

Since then, the US has generally worked to facilitate trade among nations, passing the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act of 1934. Subsequent involvement in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT, founded 1947) and its successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO), have focused on liberalizing trade among nations.

Regional Trade Agreements

Today, numerous regional trade blocs exist among countries of various regions, designed to reduce trade barriers among the participating countries. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is one example, designed to reduce trade barriers among Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The European Union (EU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are other examples of regional trade blocs.

Section 04: US Trade

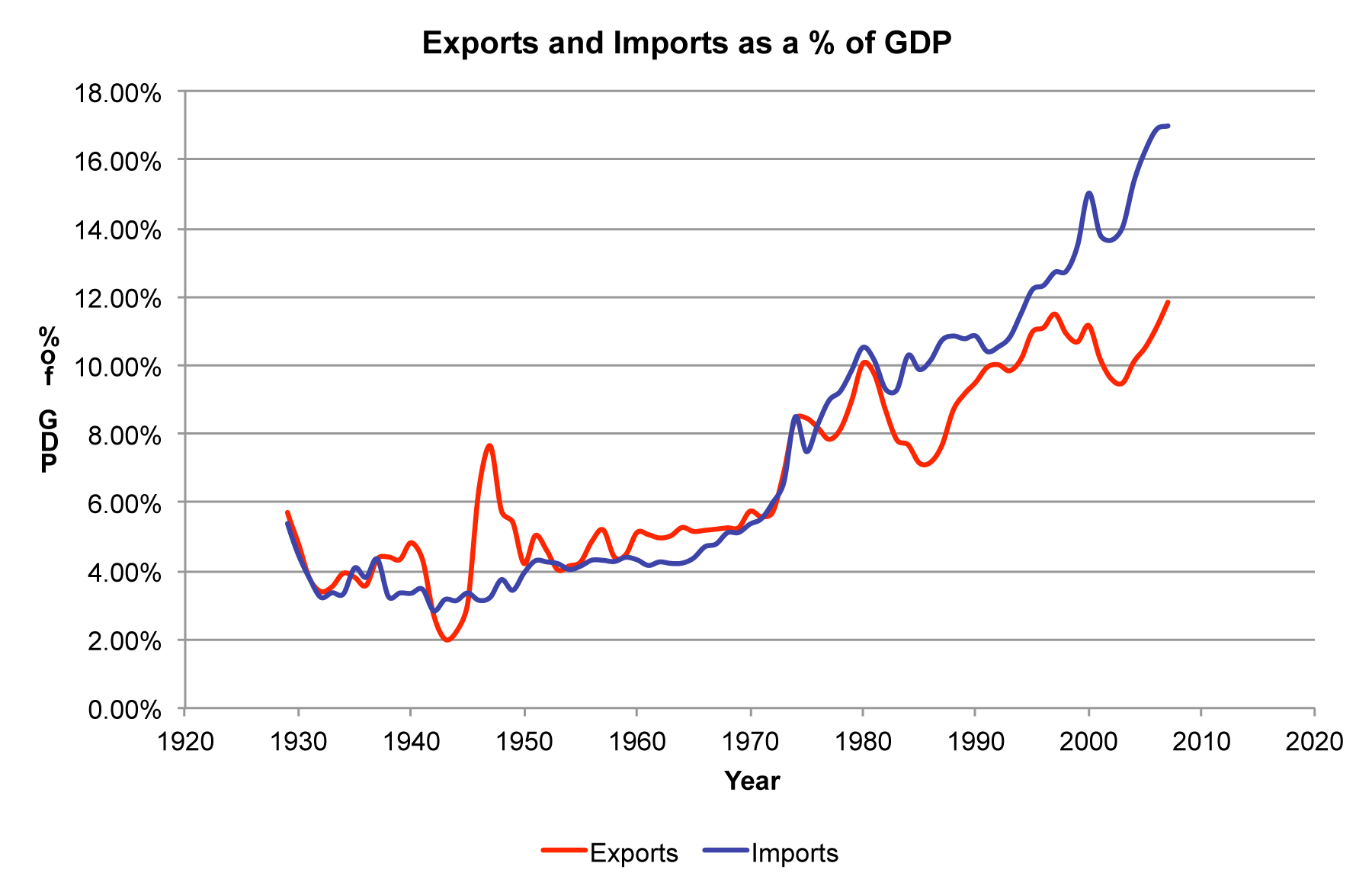

The United States economy is closely tied to global markets, with imports equivalent to 17% of our GDP and exports almost 12% of our GDP. With such close ties, it has been said that when the US economy sneezes, the world catches a cold.[2]

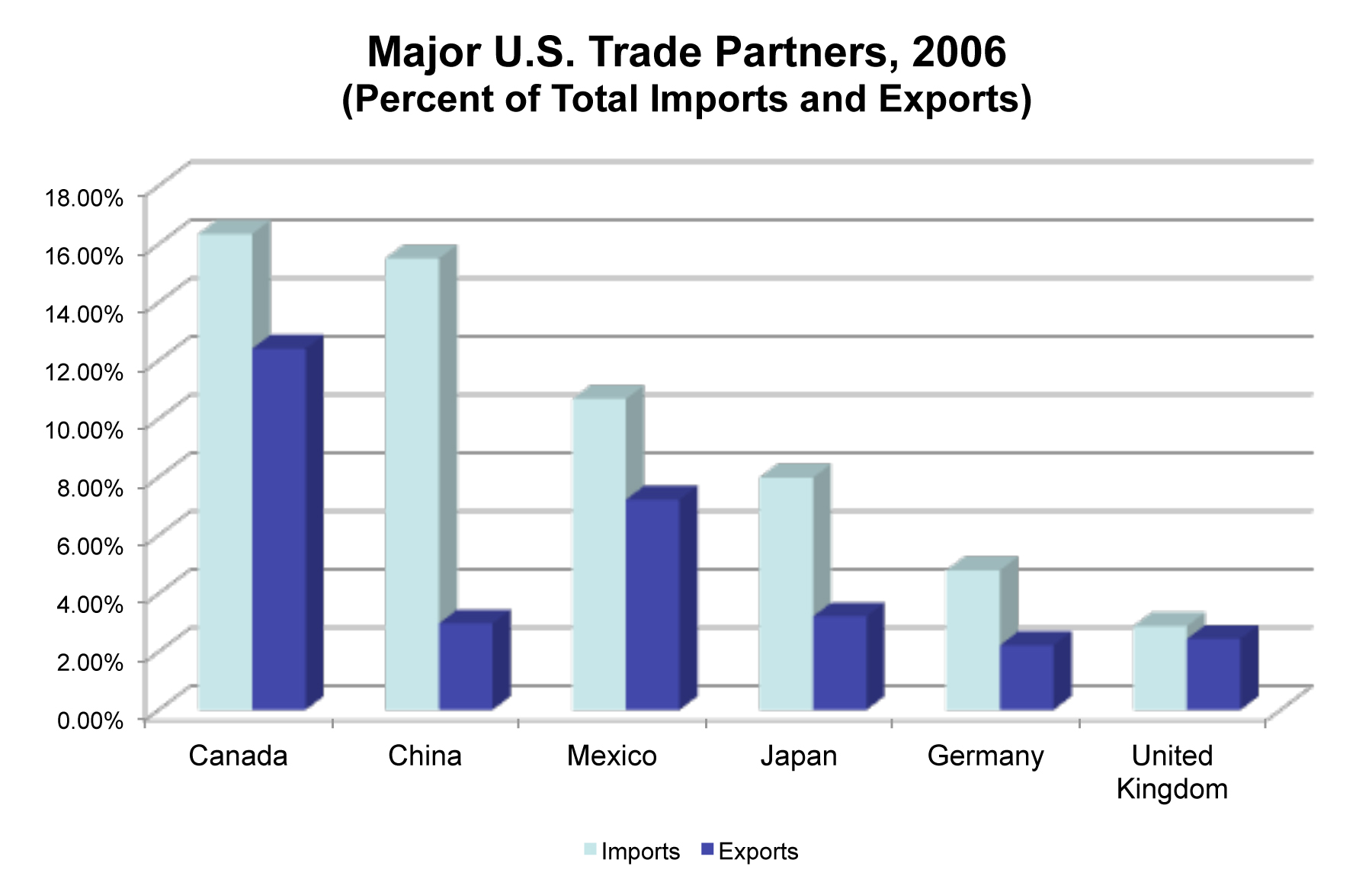

Major trading partners with the United States include Canada, China, Mexico, Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Over one-fourth of US imports are from Canada and Mexico, partners with the US in NAFTA. China continues to be a significant trade partner, particularly for imports. Japan and Germany, once arch-rivals in World War II, are now key trade partners with the United States.[3]

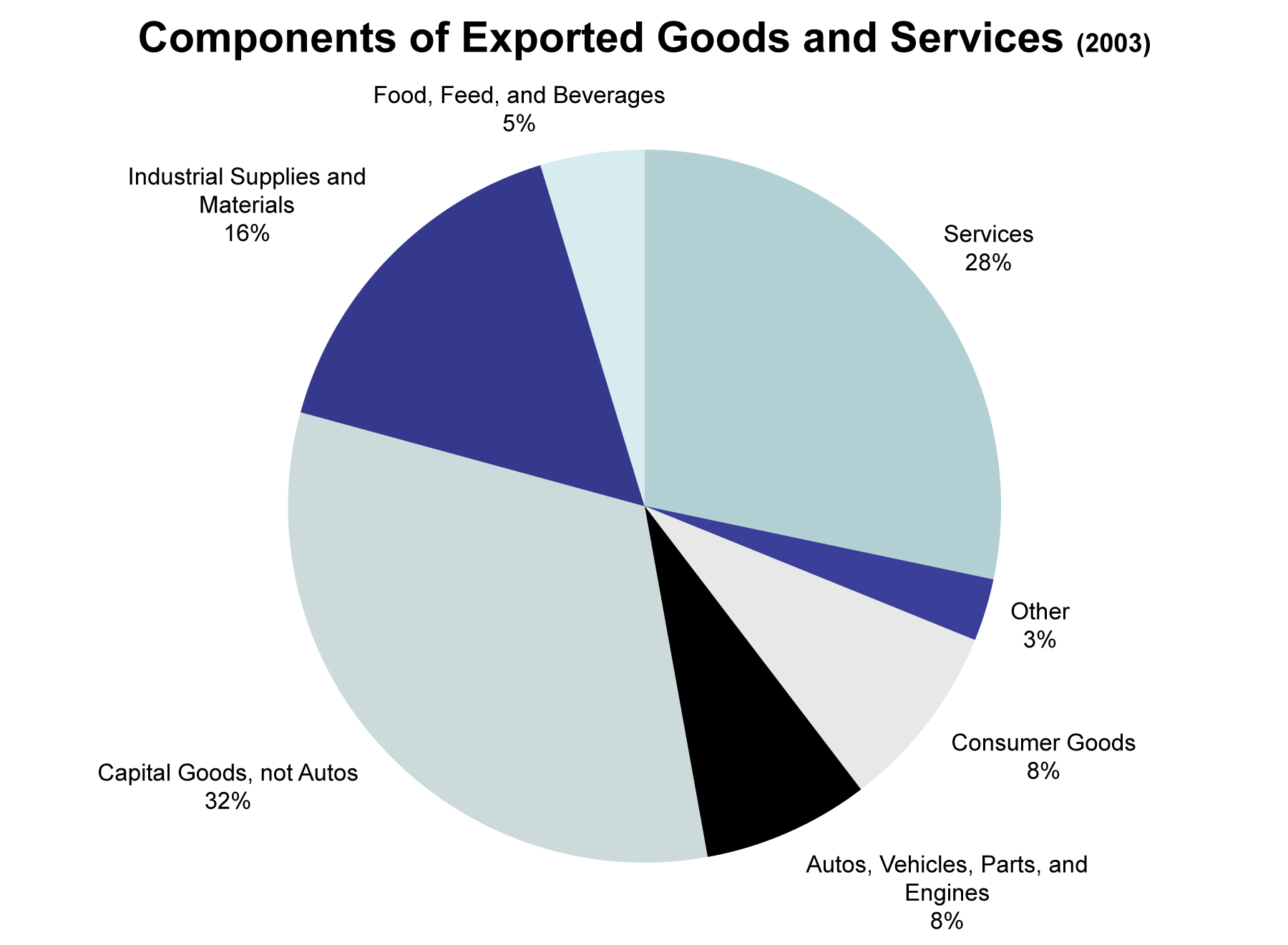

The following pie chart shows the components of the goods and services exported by the United States [4]:

Here is the breakdown of the goods and services imported by the United States [4]:

Importing and Exporting Services

Unlike a good that can be produced and then shipped from one country to the next, services are often consumed at the point of production. Exported and imported services could include banking or financial services, air travel, tourism, or entertainment. If a Japanese citizen came to the United States and flew using an American airline, then went to see a play on Broadway, the US would be exporting services. Similarly, when Americans travel abroad on foreign-owned airlines and go sightseeing, we are importing services.

Section 05: Conclusion

Trade improves the economic well-being of individuals, and often the political relations among the different countries:

And it came to pass that the Lamanites did also go whithersoever they would, whether it were among the Lamanites or among the Nephites; and thus they did have free intercourse one with another, to buy and to sell, and to get gain, according to their desire.

And it came to pass that they became exceedingly rich, both the Lamanites and the Nephites ...

— Helaman 6:8–9; emphasis added

Notes

- ^ For more information on the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1934, see www.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/id/17606.htm; also historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/from_war_to_war/reedsmootandthesmoot-hawleytariff1930.html

- ^ Chart from Federal Reserve: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/categories/18

- ^ Chart from Office of Trade and Industry Information (OTII), Manufacturing and Services, International Trade Administration, US Department of Commerce: http://tse.export.gov

- ^ Chart from National Council on Economic Education: http://www.econedlink.org/lessons/EM538/docs/EM538.pdf