Banking

Section 01: The Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System (sometimes called the Fed) was established by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. The Fed is the central banking authority of the United States. The governing authority of the Federal Reserve System is called the BOARD OF GOVERNORS. There are seven members of the Board of Governors, each is appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate for 14-year terms. The chairman and the vice chairman are appointed for four year terms from among the seven governors. The primary policy making body of the Federal Reserve is called the Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC. The FOMC is comprised of the Board of Governors plus five of the 12 Presidents of the Regional Federal Reserve Banks. One of the five regional presidents is always the President of the New York Fed, and the other four rotate among the other 11 presidents. The FOMC sets policy on the purchase and sale of government bonds in the open market. As will be seen later, this is the most important control over the money supply.

The Twelve Federal Reserve Banks

One unusual feature of the Federal Reserve System in the United States is that we really have 12 central banks. Most countries have only one central bank. Our system is divided into 12 regional banks, approximately representing equal divisions of the population in 1913, but today do not all make as much sense. There are 12 regional banks because many western and southern states did not trust the “eastern establishment” represented by such tycoons as J.P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. In order to gain support for the Federal Reserve Act, it was necessary to disperse the power of the Federal Reserve System throughout the country and to give control of the system to a board that was appointed and confirmed by the government.

The Fed is sometimes called a quasi-public bank. It really is quite a unique business model. The regional banks are privately owned but publicly controlled. The banks are privately owned by the private banks within their regions. All nationally chartered private banks and many state chartered banks own stock in the federal reserve bank in their region. The model is unique because the owners of the bank do not control the bank or its policies. They do not even receive all of the profits from the operation of the bank. Member banks receive a dividend that is equal to 6% of their stock, and the remainder of the profits of the Federal Reserve banks goes to the US Treasury. In 2010, the member banks received 1.583 billion dollars, and the US Treasury received 79.268 billion dollars.

The Federal Reserve Banks are also called Bankers’ Banks. Individual United States citizens cannot have an account at the Fed. Member banks do have an account and can make deposits and withdrawals, can borrow money from the Fed, and receive their Federal Reserve Notes from their regional bank. You can look at a one dollar bill and see which Federal Reserve Bank issued that bill. At the center left of the bill, you will see a letter of the alphabet that corresponds to the regional bank that issued the bill. A is for 1, the Boston Bank. B is for 2, the New York Bank. C is for 3, the Philadelphia Bank, etc. Many of the bills in the Western United States have an L for the 12th bank in San Francisco. Another interesting feature of our system is that the Federal Reserve System issues our money, but the money is actually created by the US Treasury. The Bureau of the Mint creates our coinage and the Bureau of Printing and Engraving creates our paper money. The Fed then purchases the coinage at face value and the paper money at approximately six cents per bill, regardless of the denomination of the bill, and issues the money to the various regional banks.

Section 02: Banking is a Business

Bankers provide services and attempt to make a profit for their owners. The Balance Sheet of a Commercial Bank looks much like the balance sheet of any other business. Assets are items the bank owns and Liabilities are items the bank owes. Assets minus liabilities equal the net worth of the bank. It may seem counterintuitive, but the liabilities of the banks are its deposits, and the assets of the bank are the loans that it has issued. Remember that a liability is something that the bank owes; when you deposit money into your account, the bank owes you that money. An asset is something that the bank owns; when the bank lends you money, it owns that loan, and you owe the bank the amount of the loan. Banks like to make loans, because it is one of the primary ways that they make money. Charging interest on the loan is one of the most profitable activities for any commercial bank.

Reserves are the funds or assets that banks hold in the form of cash, or on deposit with the central bank. Why would a bank hold reserves in the vault when they could be lending that money out and earning interest? The bank has to have enough money on hand for day to day operations. If someone comes into the bank and wants to withdraw $1,000 from her savings account, it would not look good if the bank had to say, “Sorry, we don’t have $1,000 right now. Could you come back later today?” They want to always have enough money on hand to do their daily business, so even though money in the vault is “sterile” in the sense that it does not earn any interest for the bank, it still is a good business practice to have money available to meet customer needs.

The other important reason that banks keep money in reserve is that they are legally required to do so. The percentage of the deposits that must be kept in reserve is called the reserve ratio. We’ll talk a lot about that in the next section and in our later discussion of monetary policy.

Fractional Reserve Banking

Our modern banking system is known as fractional reserve banking. “Fractional reserve” refers to the fact that, at any given point in time, the bank has in reserve only a fraction of its total deposits. This system was developed as early as the middle ages to allow banks to invest money (or make loans) for a profit. If banks were forced to keep all of their deposits in reserve in the vault, then the bank would be no more than a storage unit for customers’ money. Not only could they not make any money, but they would not be able to pay interest to their depositors. In fact, in order to operate, they would have to charge customers a fee for accepting their deposits.

In this system, the Federal Reserve sets legal reserve requirements as a means of controlling the money supply. An illustration will help you see how the reserve requirement is used to control the money supply, and also how the commercial banking system of the United States “creates” money.

In this example, we are going to consider the actions of a fictional bank called The Last National Bank (LNB) which has a legal reserve requirement of 10%. This bank’s initial balance sheet is shown below:

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Reserves: $1,000 | Deposits: $1,000 |

Notice that this bank has liabilities of $1,000, the total of its deposits. If the bank initially takes this deposit and puts it in the vault, then it also has assets of $1,000 in the form on cash reserves. If the reserve requirement is 10% then the LNB is only legally required to keep $100 in reserve. What should the bank do with the other $900? Well, don’t forget that this bank has to make a profit just like any other business, so it needs to do something with the $900 that will bring in more money than what it is paying to the depositor in interest. The bank could invest the $900, or lend it and charge more interest than what it is paying to the depositor. In either of these two scenarios the result will be the same, but we will look at the case where the bank lends out the money. After the loan is made, the balance sheet of the LNB looks like the following:

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Reserves: $1,000 | Deposits: $1,000 |

| Loans: $900 |

Let’s say that the person who borrows the $900 buys an item from someone, who then deposits the $900 in his bank, The Second to the Last National Bank (SLNB). The balance sheet for the SLNB is illustrated below. Notice that deposit is a liability to the bank and, at least initially, we are showing the entire deposit as being held in reserve as cash vault, which is an asset to the bank.

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Reserves: $900 | Deposits: $900 |

The SLNB does not have to keep $900 in reserves, however. Because the legal reserve ratio is 10%, SLNB can lend out $810. If the SLNB has $900 in deposits and $900 in “actual” reserves with a 10% reserve ratio, they have what is call “excess” reserves of $810. The “required” reserves would be $90, and they can lend out all of their excess reserves. After making such a loan, the new balance sheet for the SLND would look like the following:

| Assets | Liabilities |

|---|---|

| Reserves: $900 | Deposits: $900 |

| Loans: $810 |

Notice what has happened to the money supply as a result of this fractional reserve banking system. Remember that the money supply includes cash in the hands of the non-bank public plus demand deposits at commercial banks. When the original deposit is made at the LNB, the money supply is $1,000. When the LNB lends $900 the, money supply immediately goes up to $1,900. Even if the person who borrowed the $900 just kept the money in his pocket this would be true. The money supply expands, however, when the $900 is deposited into the SLNB and they make an $810 loan off that deposit. Now the money supply is $1,000 + $900 + $810 = $2,710. When the $810 is deposited into another bank and they lend out 90% of that deposit the money supply continues to grow. The commercial banking system is essentially “creating” money. The maximum amount of money supply expansion that can exist in the banking system is equal to:

Total Potential Money Expansion = Excess Reserves x 1/rr

where “rr” is the legal Required Reserve Ratio. “1/rr” is referred to as the simple money multiplier. “rr” is the Bank’s Required Reserves divided by the Bank’s Liabilities. In our example rr = 0.10 so 1/rr = 10. Since the initial excess reserves of the LNB were equal to $900, the total potential money expansion would be equal to $900 x 10 = $9,000.

Notice: the total potential money expansion is equal to excess reserves times 1/rr. This is the potential, because you will only get this amount of money expansion under two critical conditions: First, the bank must keep only the minimum amount of reserves on hand and lend out all of their excess reserves, and second, the total amount of each loan in the expansion process must be deposited into another bank. If the reserve ratio is 10% but a bank decides to keep 15% instead, you do not reach the full potential of expansion. This would be true because the bank is keeping excess reserves. Also, if a person borrows $900 dollars but deposits less than that amount in his bank, and keeps some in cash hidden under his mattress, you will not have the full potential money expansion. This would be true because the excess reserves of one bank are not all becoming deposits in another bank.

Summary

- Banks can create money because of the fractional reserve banking system.

- The Federal Reserve controls the ability of banks to expand the money supply by setting the reserve ratio.

- Commercial banks hold reserves as cash and do one of two things with their excess reserves: Lend them out or invest them in government securities.

- In both cases, the excess reserves of one bank become the deposits of another bank.

- The total potential expansion of the money supply will be equal to excess reserves times 1/rr.

- The Fed uses the reserve ratio as one of the tools of Monetary Policy.

Return to the course in I-Learn and complete the activity that corresponds with this material.

Section 03: Monetary Policy

The Federal Reserve has control over the three primary instruments of monetary policy:

- Open-market Operations

- Reserve Requirements

- Discount Rate (note the difference between this and the Federal Funds Rate)

Open Market Operations

Open Market Operations refers to the buying and selling of government bonds by the Federal Open Market Committee. When the FOMC decides to buy bonds they take bonds out of the hands of the public and put cash into the hands of the public. If the Fed were to buy a bond from you, you would give the Fed the bond and they would give you cash. Since bonds are not part of the money supply but cash is, the money supply would immediately increase by the amount of the cash that you are given. The cash would have formerly been in a Fed vault and therefore would not have been part of M1. If you take that cash and deposit it in a bank, bank excess reserves go up and the potential increase in the money supply grows through the money creation process described in the previous section. For example, if the reserve requirement were 5%, the multiplier would be 20—if the Fed buys $2 billion in bonds, the money supply will go up by $40 billion.

If the Fed were to sell bonds, you would give the Fed cash and they would give you bonds. The cash that was formerly in your hands (or in your bank account) was part of M1, but as soon as the Fed gives you a bond and you give the Fed your money the money, supply immediately falls. If you take the money to pay for the bond out of your bank account, excess reserves will fall and the money contracts by a multiple of the reduction in excess reserves. Think of the opposite of money creation—in fact, it is sometimes called destroying money. For example, if the reserve requirement were 10%, then the multiplier would be 10 and if the Fed sells $1 billion in bonds, the money supply decreases by $10 billion.

The Reserve Requirement

Within limits established by Congress, the Federal Reserve has the discretion to raise or lower the legal reserve ratio for commercial banks. Recall that if the Fed reduces the reserve ratio, then banks will have additional excess reserves that they can lend out, and the money supply may be expanded by an amount equal to excess reserves times 1/rr. Increasing the reserve ratio will reduce the amount of excess reserves that banks can lend out and will result in a contraction of the money supply by an equivalent amount. Therefore, the ability to set the reserve ratio becomes an instrument of monetary policy to the extent that the reserve ratio effects the money supply.

Discount Rate Policy

What would happen to a commercial bank that lends out so much money that they do not have enough on hand to meet their required reserves? In other words, in our example of the LNB that had required reserves of $100 and could lend out $900, what would happen if the bank made of loan of $950 and found at the end of the day that they only had $50 in actual reserves? When commercial banks are short on reserves, they can borrow from a Federal Reserve Bank. The interest rate they are charged on such a loan is called the discount rate.

When the discount rate is low, the Fed encourages borrowing by member banks, which tends to expand the money supply. If I lend out $50 dollars too many to a bank customer and charge him 6% interest, and the Fed sets the discount rate at 2%, it makes sense for me to just borrow the $50 from the Fed to make up my required reserves. In effect, low discount rates encourage commercial banks to loan out their required reserves and then borrow the reserves back from the Fed. Obviously, the more loans that banks make, the higher the money supply, as discussed in the section on money creation.

When the discount rate is high, the opposite is true. High discount rates discourage banks from borrowing from the Fed, and banks will therefore be more cautious in making loans. As banks make fewer loans, the money supply falls. Because the money supply rises or falls as the discount rate is lower or higher, the discount rate becomes an instrument of monetary policy. The Feds ability to manipulate the discount rate allows it to also manipulate the money supply.Important Note: You should not confuse the Discount Rate with the Federal Funds Rate. The discount rate is the interest rate that the Federal Reserve charges member banks when these banks borrow money from the Fed. The Federal Funds Rate is the rate that one commercial bank charges another commercial bank when banks borrow money from each other. The Federal Funds Rate is sometimes called an overnight rate because banks usually borrow money from each other for very short periods of time—sometimes just overnight.

Return to the course in I-Learn and complete the activity that corresponds with this material.

Section 04: The Money Market Revisited

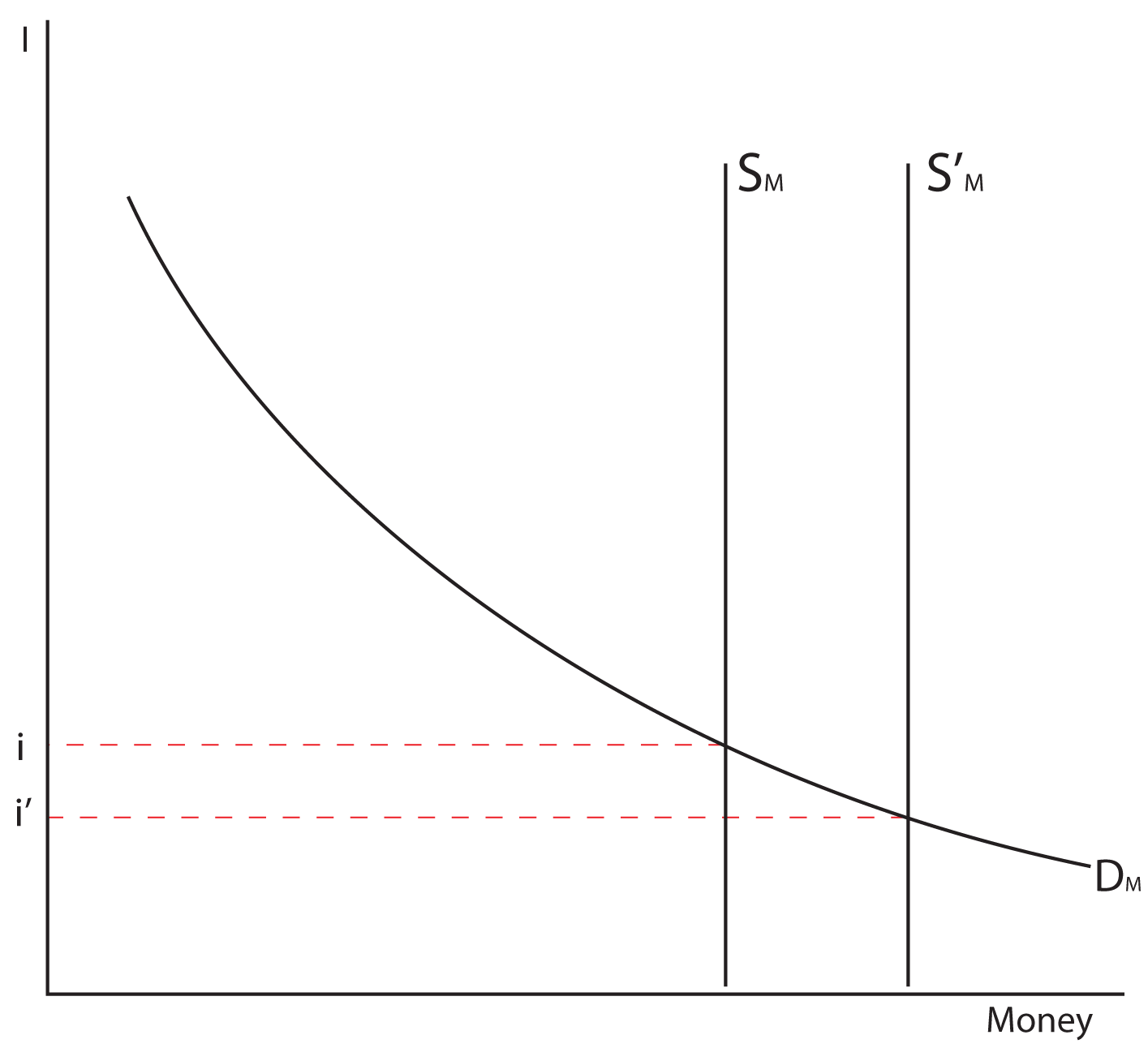

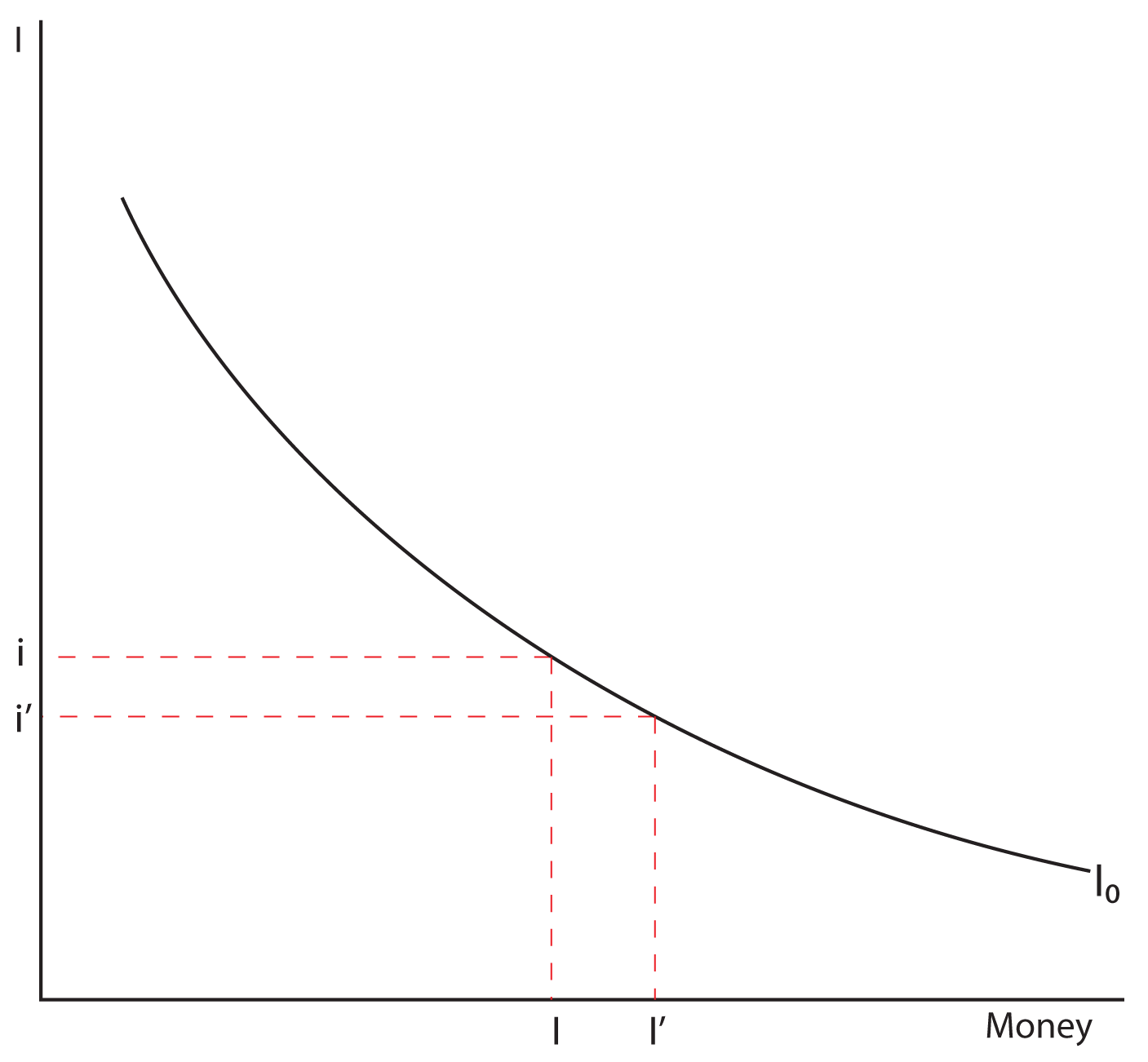

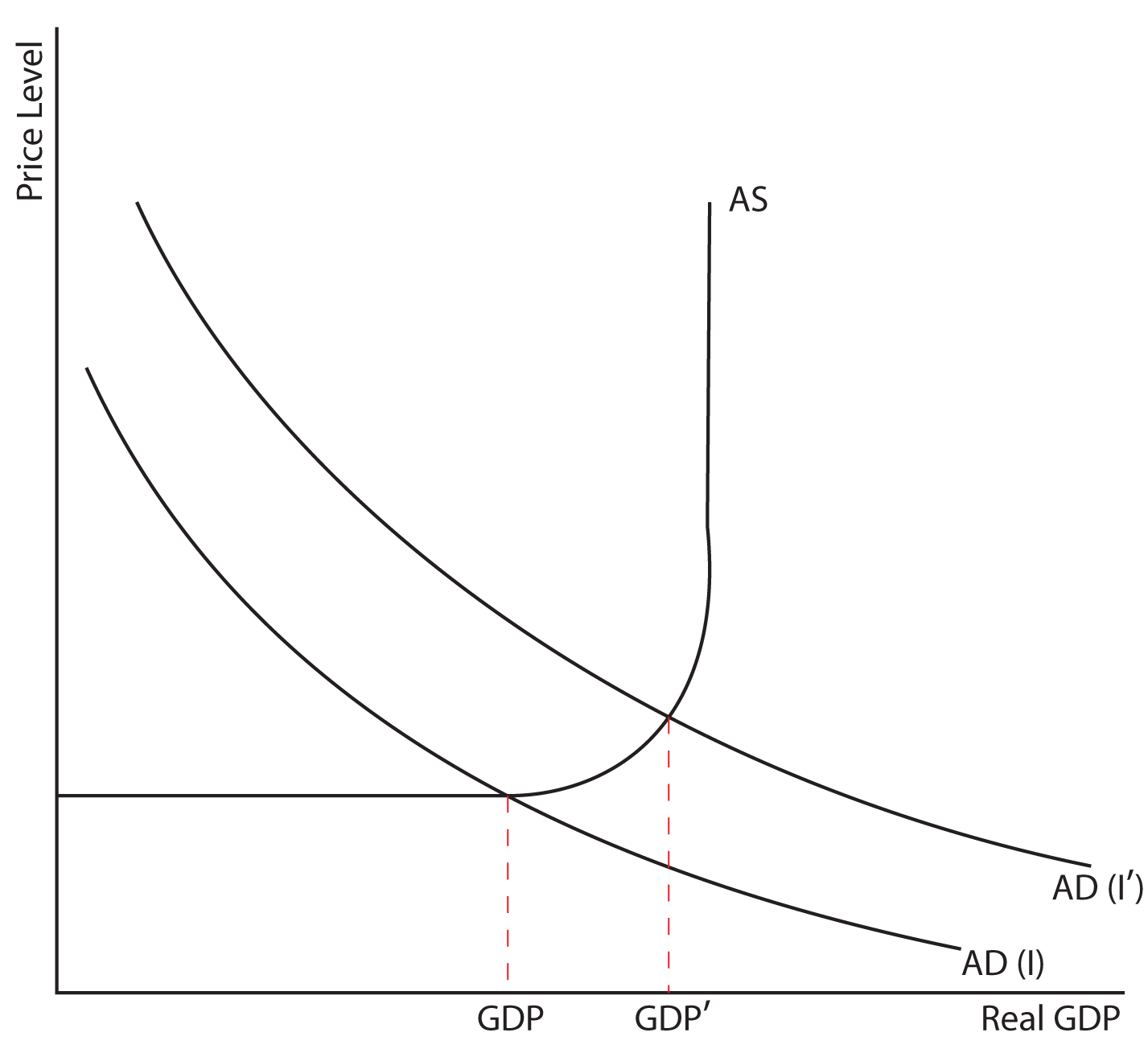

A decrease in the money supply would cause the interest rate to rise; an increase in the money supply would lower the interest rate. The change in the interest rate as the Fed exercises monetary policy will either increase investment and interest sensitive consumption (if the interest rate falls) or decrease investment and interest sensitive consumption (if the interest rate rises). Since investment and consumption are two components of Aggregate Demand, a change in investment and consumption will either stimulate (if investment and consumption go up) or contract (if investment and consumption go down) AD.

Shifting AD to the right will expand the economy, causing inflation in the Intermediate or Classical ranges of AS, while increasing output or GDP and lowering unemployment in the Keynesian or Intermediate ranges of AS. Shifting AD to the left will contract the economy, reducing inflation in the Intermediate or Classical ranges of AS and decreasing output or GDP, while increasing unemployment in the Keynesian or Intermediate ranges of AS. Let’s review the exact process:

Expansionary Monetary Policy

If the Fed thinks that unemployment is rising too sharply, it will follow an expansionary monetary policy designed to stimulate output and reduce unemployment.

Think About It: Expansionary Monetary Policy

The following outlines the steps of expansionary monetary policy. Consider the following questions before checking the answers by clicking in the word in parenthesis:

- The Fed can increase excess reserves ( How? ), which

- increases the money supply ( Why? ), which

- decreases the interest rate ( Why? ), which

- increases I and C ( Why? ), which

- increases AD ( Why? ), which

- increases Real GDP, and decreases Unemployment and the Price Level

( When? ).

Contractionary Monetary Policy

If the Fed thinks that Inflation is too high in the economy, they will follow a contractionary monetary policy designed to reduce the price level.

Think About It: Contractionary Monetary Policy

The following outlines the steps of contractionary monetary policy. Consider the following questions before checking the answers by clicking in the word in parenthesis:

Section 05: Summary

We can summarize the relationship between the money supply and AD as follows:

- Increases in the Money Supply lead to an increase in AD, because interest rates will fall.

- Decreases in the Money Supply leads to a decrease in AD, because interest rates will rise.

We can summarize the relationship between the money supply and the Price Level as follows:

- Increases in the Money Supply leads to increases in the Price Level.

- Decreases in the Money Supply leads to decreases the Price Level.

Return to the course in I-Learn and complete the activity that corresponds with this material.