Section 01: Monopolistic Competition

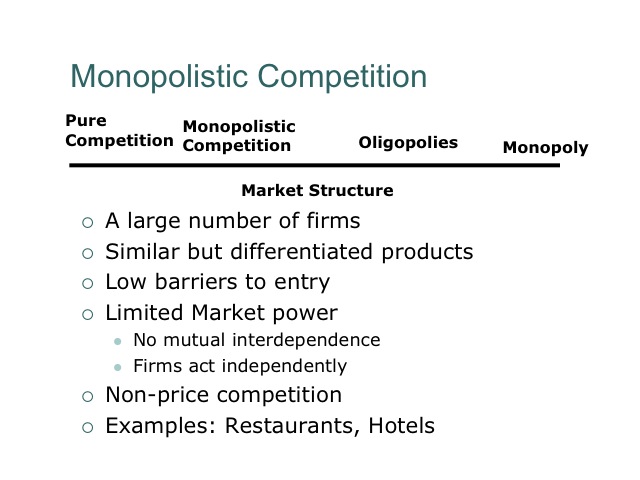

We now turn our attention to one of the industry structures that fall between pure competition and monopolies. In monopolistic competition, there are a large number of firms with lower barriers to entry. Each firm’s product is unique but very similar to those produced by other firms. For example, only one firm produces the Big Mac or the Whopper but there are many products similar to each. Since the barriers to entry are low and the products each firm produces are similar, firms have a limited degree of market power. With a large number of firms there is no mutual interdependence among firms so each firm acts independently. The demand curve for each firm is highly elastic, since there are many close substitutes but not perfectly elastic, since each product is differentiated. Firms undertake substantial non-price competition or advertising in monopolistic competition allowing them to compete on the features of their product rather than solely on price.

Firms in monopolistic competition may attempt to create a niche market and service only a small segment of the entire market. Some firms in pure competition attempt to move into the monopolistic competition by differentiating their product. For example, Reed’s Dairy in Idaho Falls has successfully moved into the monopolistic competitive market by offering hormone free milk and home delivery milk, cheese, and ice cream.

So how can a firm in monopolistic competition, differentiate their product?

The more a firm is able to differentiate its products from those of competitors, the greater its ability to set the price above marginal cost. If the market niche is too narrowly defined, the firm may not be able to attract enough customers; too broad and the firm faces greater competition. Product differentiation can be real or perceived.

Real product differentiation can take place in a variety of different methods: First, a product can be differentiated based on its physical characteristics, such as liquid gel tablets pain medication or a perfume that has a different smell. The location of the product, such as locating a gas station or hotel close to the interstate, differentiates the good from other competitors located in more remote areas and allows the firm some additional price control. A firm may also differentiate the product by the other features or service it provides. For example, a furniture store might offer free delivery and set up of its furniture or offer warrantees or money back guarantees if not satisfied with the product. A food company may offer its products in ready to serve packages or easy open cans. A firm may differentiate its product based on the method of production it employs, such as using a certain percentage of recycled material or pursing other environmentally friendly methods to produce a “green” product. Buc-ee’s, a chain of gas stations in Texas, for example, has successfully differentiated itself by providing clean private bathrooms. Watch the following video clip: http://abcnews.go.com/Video/playerIndex?id=8999959.

Perceived Product Differentiation

Other product differentiation is not real but perceived in the minds of consumers which is often accomplished through advertising and celebrity endorsement. To the extent that firms are able to convince consumers that their product is different even if it is only in the minds of the consumers, they are able to charge a different price. An excerpt from Dave Barry’s "Twenty-five Things I Have Learned in 50 Years" highlights the role of advertising in perceived differentiation:

“The value of advertising is that it tells you the exact opposite of what the advertiser actually thinks. … If Coke and Pepsi spend billions of dollars to convince you that there are significant differences between these products, both companies realize that Pepsi and Coke are virtually identical. If the advertisement strongly suggests that Nike shoes enable athletes to perform amazing feats, Nike wants you to disregard the fact that shoe brand is unrelated to athletic ability. If Budweiser runs an elaborate advertising campaign stressing the critical importance of a beer's "born-on" date, Budweiser knows this factor has virtually nothing to do with how good a beer tastes. If an advertisement shows a group of cool, attractive youngsters getting excited and high-fiving each other because the refrigerator contains Sunny Delight, the advertiser knows that any real youngster who reacted in this way to this beverage would be considered by his peers to be the world’s biggest nerd. And so on. On those rare occasions when advertising dares to poke fun at the product – as in the classic Volkswagen Beetle campaign-- it’s because the advertiser actually thinks the product is pretty good.”

Although real and perceived product differentiation often increase the firm’s costs, consumers focus more on the features of the product than the product price making the product demand more inelastic. To the degree that they are successful, firms have greater ability to set price above marginal cost. Consumers also benefit from product differentiation since it allows them greater choice in selecting products.

Practice

1. Consider the different ways you could differentiate a hotel?

When differentiating your product, it is important to remember that it can’t be everything to everyone. Creating a market niche implies that the product focuses on meeting the particular needs of a segment of the market. A hotel located close to the airport or interstate is designed to meet the needs of individuals traveling, while a hotel located in a quite remote area focuses more on serving the needs of vacationers or honeymooners. A hotel may focus on the experience that consumers have providing luxurious accommodations, theme rooms, or private spas. Other hotels are more cost conscious and focus on providing “a good nights sleep” with few amenities. A hotel may offer a variety of services such as Wi-Fi, an exercise room, a business office, a pool, newspaper, breakfast, or shuttle to the airport. Think of four different hotels and identify the type of consumers the firm is targeting. Think of how the Ritz-Carlton differs from Motel 6.

Some firms will differentiate their products to service different markets. Hyatt Resorts and Hotels offers a variety of different hotels each focusing on a different market segment: the Hyatt Regency focuses on business meetings; the Grand Hyatt offers larger public space with a large number of rooms; and the Park Hyatt is more exclusive, having fewer rooms, and focuses on discrete pampering of their clientele. Room rates differ among these different market segments, and the hotel is able to charge each market segment based on their respective demands.

Holiday Inn researched their customer base and found that 80 percent were men and 74 percent liked to watch basketball. Instead of pillow mints or fruity hair conditioners, the hotel entered customers into a drawing for NCAA tournament tickets. The hotel also targets soccer moms offering free storage of equipment and ice for their coolers. Source: Business Week Feb. 19, 2001 p. 16

2. Consider how you could differentiate beef?

Beef exhibits more of the characteristics of pure competition, thus consumers tend to focus on the price for a given quality or cut of meat. However, the Black Angus Breed Association has successfully convinced many consumers that the black angus breed is a higher quality meat than other breeds, thus differentiating its product. Restaurants will often advertise that they serve only certified black angus. Even if there are only perceived differences in the mind of the consumer, firms gain greater price control. Kobe beef is renowned for its quality and tenderness as the wagyu breed of cattle are at times fed beer and given massages to produce meat that sells for a premium at fine restaurants in Japan and in the United States.

Others have successfully differentiated their product by certain characteristics such as organic or hormone free meat. Regional branding is another way firms have been able to differentiate their product, such as Montana Legend or Pure Wyoming Beef, Inc. Grocery stores and restaurants may differentiate beef using special seasonings, marinates, cuts or by providing the meat in special packages.

Reference:

http://www.foodmanufacture.co.uk/news/fullstory.php/aid/3838/Prime_stock_gets_beer_and_massage.html

Monopolistic Competition in the Short Run

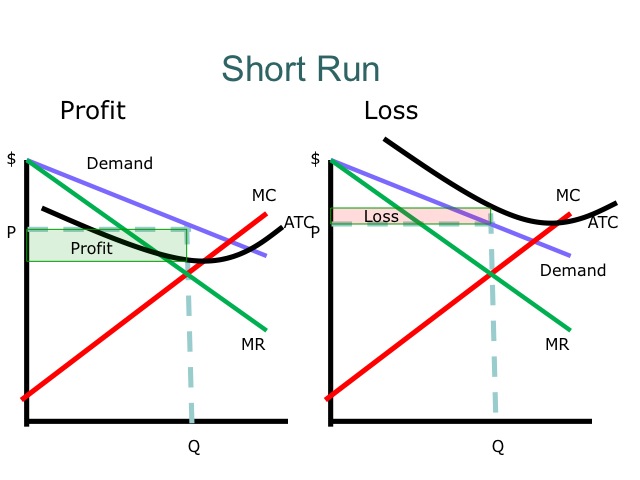

In the short run, firms in monopolistic competition may earn economic profits or losses. Firms still follow the decision rule to produce where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, provided the price is above average variable cost.

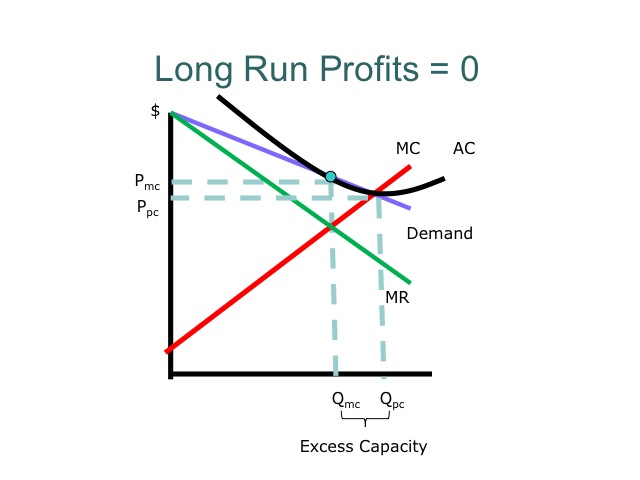

Due to the low barriers to entry, if firms are making an economic profit, other firms will enter into the market driving the profits to zero. However, because the products are differentiated, the demand curve is not perfectly elastic and so the long-run price will not equal the minimum of average total costs (as was the case in pure competition). But as entry happens, the demand for an individual firm will shift left and become more elastic. This will continue until the average cost curve just touches the demand curve in one spot (i.e. it is tangent to it). This will happen exactly at a quantity where marginal revenue equals marginal cost (Pmc, Qmc). For example, if a hotel is making an economic profit since it offers a swimming pool, other hotels will start to offer swimming pools, thus in the long run economic profits will be zero. Firms that continue to innovate can maintain short run profits but there are always pressures in the market for those profits to dissipate in the long run, leaving the firm with a normal profit.

Monopolistic Competition in the Long Run

Compared to the benchmark of pure competition, monopolistically competitive markets produce a lower quantity and charge a higher price. Firms in monopolistic competition are not productively efficient since they are not producing at the minimum average cost. Firms have excess capacity, which is the difference between the profit maximizing quantity and the productively efficient quantity that would allow them to produce at the lowest average cost. A firm could expand its output and lower the average cost per unit. Firms are also not allocatively efficient since price is greater than the marginal cost on the last unit produced. In spite of these losses, society does benefit from being able to purchase a range of differentiated products, real or perceived.

Oligopolies

Oligopolies have a few large firms and may produce either a standardized product, such as steel, or a differentiated product, such as automobiles. There are significant barriers to entry which limit the number of firms that can enter the market often due to the cost structure of the industry. Since there are only a few firms, the market power of a firm depends on the actions of the other firms in the industry. Consequently, firms tend to compete heavily on non-price items, such as the features of the product. Oligopolies fall between monopolistic competition and monopolies on the industry structure continuum.

View the following video discussing the auto industry. Although the video is dated, the concepts are still relevant.

Video on oligopolies in the auto industry (about 6 minutes)

Measuring Market Concentration

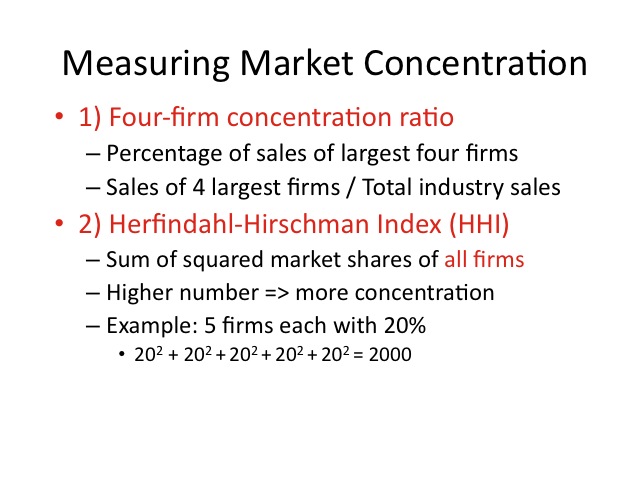

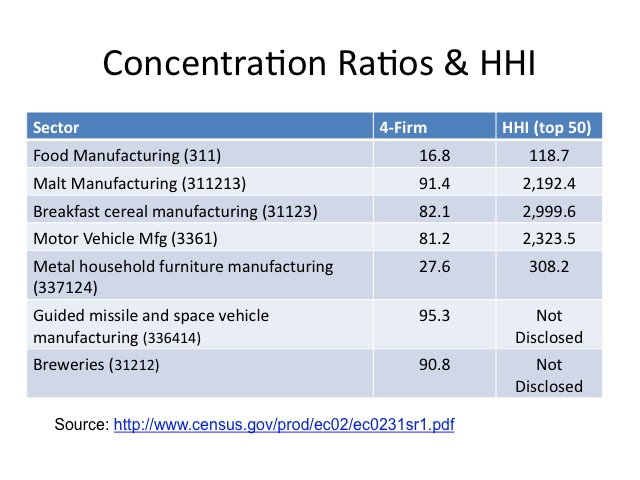

With a relatively few number of firms in the industry, firms often have an incentive to collude and act like a monopoly. Consequently, the government measures the amount of concentration that exist in a market or that would exist if a merger were to take place. The two common measures are the four-firm concentration ratio and the Hefindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). See: http://www.census.gov/epcd/www/concentration.html

The four-firm concentration ratio sums the market share of the four largest firms in the industry based on output. An industry in pure competition would have a very low concentration ratio. Industries in monopolistic competition typically have a concentration ratio less than 40, while oligopolies have a ratio greater than 40, such as the airline manufacturing industry.

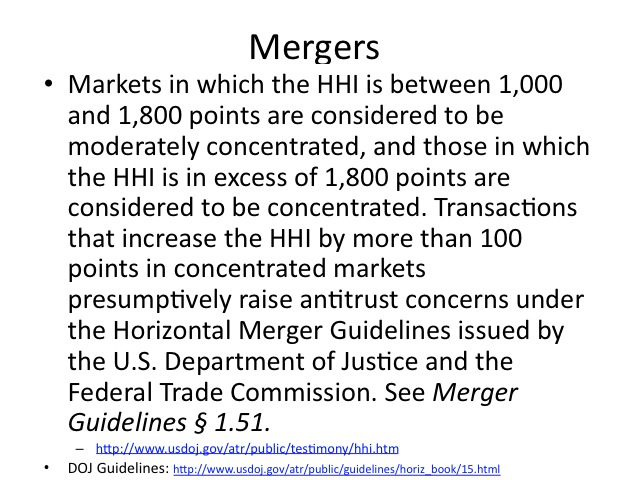

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, often shortened to the Herfindahl Index or HHI, takes the percent of the market share of each firm, squares their values and sums them. According to the Department of Justice: “The HHI takes into account the relative size and distribution of the firms in a market and approaches zero when a market consists of a large number of firms of relatively equal size. The HHI increases both as the number of firms in the market decreases and as the disparity in size between those firms increases. Markets in which the HHI is between 1000 and 1800 points are considered to be moderately concentrated, and those in which the HHI is in excess of 1800 points are considered to be concentrated.” Source: http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/testimony/hhi.htm

The more specific the industry definition, the greater the market concentration. For example, the food manufacturing industry as a whole has a low level of market concentration, however, there is significant market concentration in certain subsectors such as malt manufacturing and breakfast cereal manufacturing.

In the breweries industry (31212) which consists of establishments primarily engaged in brewing beer, ale, malt liquors,

and nonalcoholic beer, the four-firm concentration ratio is 90.8. “From 1947 to 1995, the number of American brewers fell by more than 90 percent. Though a surge in craft producers followed, few compete directly with mass-market suds like Budweiser or Miller.” Source: http://dealbook.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/27/rising-beer-prices-could-hint-at-oligopoly/

Practice

Compute the four-firm concentration ratio and HHI for each of these industries.

1. Monopoly

2. One firm with 50% and two firms each with 25%

3. One firm with 70% and six firms each with 5%

4. One hundred firms each with one percent of the market.

Try to figure out the answer to these four questions on your own before you proceed to read the answers.

Answers

1. – 100% & 1002 = 10,000

2. 100% & 502+252+252= 3,750

3. 85% & 702+(52*6) = 5,050

4. 4% & 12*100 = 100

As government seeks to enforce antitrust laws, it often faces the challenge in defining the relevant market. The broader the market is defined, the lower the level of market concentration. “When Coca-Cola Co. sought to buy Dr Pepper in the mid-1980s, its experts argued in court that their market should include not just soft drinks but all potable liquids sold in North America, including water. The approach was dubbed the ‘Lake Erie defense’.” (Sirius-XM's Fate Hinges on Definitions; If Satellite Radio Is Part Of a Broader Market, Deal May Pass Muster, Amy Schatz and John R. Wilke. Wall Street Journal. (Eastern edition). New York, N.Y.: Feb 21, 2007. pg. B.4).

Although the concentration ratio and HHI are useful measures, they fail to account for market concentration in local markets and foreign competition. Nationally, the HHI for readymix concrete manufacturing is 63.1; however, locally the market is often characterized as a monopoly or oligopoly with only few firms.

The guidelines from the Department of Justice focuses on horizontal mergers. Vertical mergers can also increase the market power of a firm, but are not as closely scrutinized as horizontal mergers.

For more oligopoly examples go to: http://www.oligopolywatch.com/

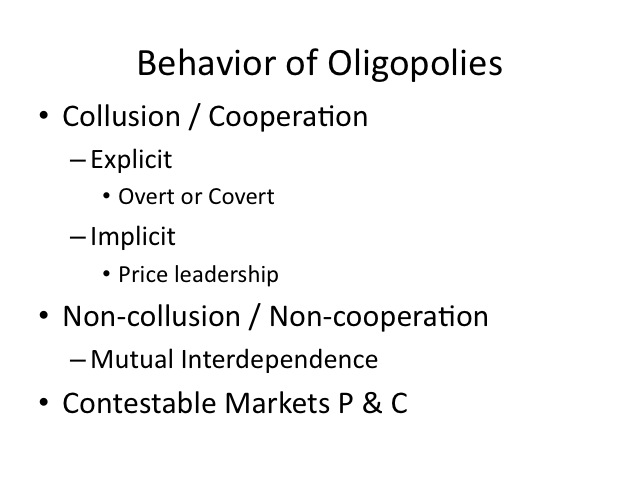

No one model explains the behavior of oligopoly.

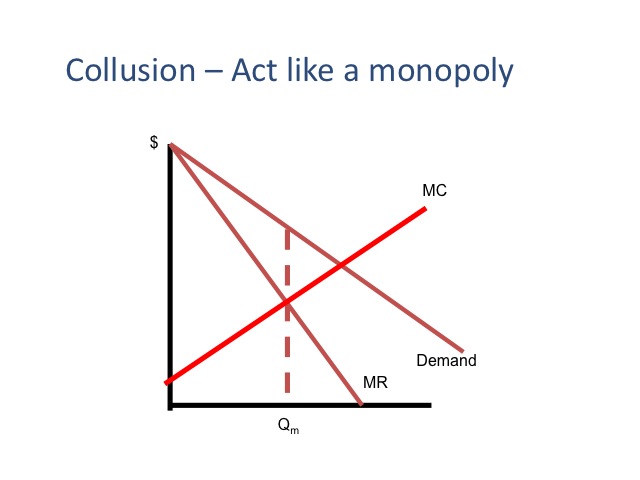

Firms may collude to set price or output levels and act like a monopoly to maximize the joint profits of firms. Collusion may be formal and explicit as is the case with Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) where members formally hold meetings to determine output levels of oil. Firms may set prices, determine output levels, or divide the market into separate geographic regions and agree not to compete with each other.

Since, collusion is illegal in the United States, Canada, and the European Union, firms may choose to secretly get together or communicate to set prices and divide up the markets, hoping to avoid the scrutiny of the government. For an example of this, view the following video:

Identical Bidding on Contracts with Tennesee Valley Authority (About 9 minutes)

In certain industries, firms choose to legally collude by following the behavior of the dominant firm. The airlines industry is a prime example, where a certain carrier will announce a price increase on tickets during certain days around holidays, a fee per suitcase or for meals. Often the price increase, will not take place for several months allowing other carriers to also announce price increases. If other carriers fail to raise their prices, the dominant firm will typically recall the price increase, not wanting to charge a higher price than competitors. These price increases may be made through the public media or in industry publications. Firms are not illegally colluding but still able signal their desire to raise prices.

According to Jonathan B. Baker, market coordination can lead to profits similar to those of collusion. “Ironically, antitrust enforcement against traditional conspiracy has produced a teaching device that business schools routinely use to show budding executives exactly how to coordinate without reaching agreements. I refer to the government’s famous Electrical Equipment cases of 35 years ago. After their indictments and convictions, the firms introduced a number of practices, unilaterally, to improve their prospects of reaching consensus by simplifying their strategies and to discourage deviation . No longer were bids assigned by the phases of the moon and a series of secret meetings. But by standardizing product definitions, distributing price books, and committing to “most favored customer” protections, they succeeded in lifting prices back up toward where they had been when the firms were conspiring overtly.”

Source: http://www.ftc.gov/speeches/other/confbd4.shtm

In addition to the antitrust laws, making collusion illegal, an industry may have difficulty trying to collude if the firms have a different demand or cost structure. If a firm is able to produce at a lower per unit cost than others, it has less of an incentive to collude. Although substantial profits may be earned by colluding, there are potentially even greater profits if firm fails to stick with the agreements. We will demonstrate this later when we discuss game theory.

The following web page contains an example of price fixing in chocolate.

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23148938/

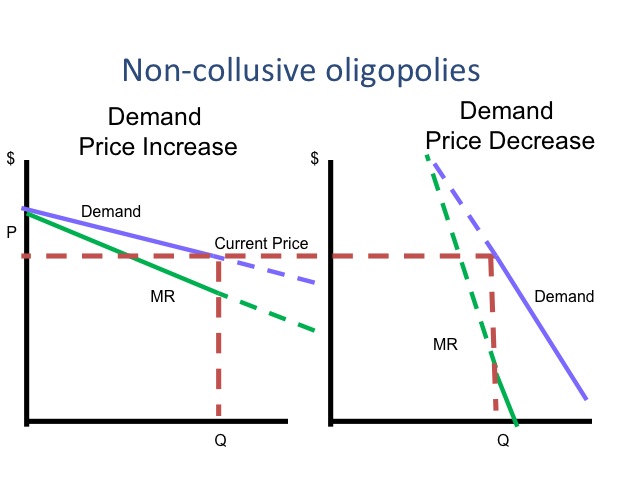

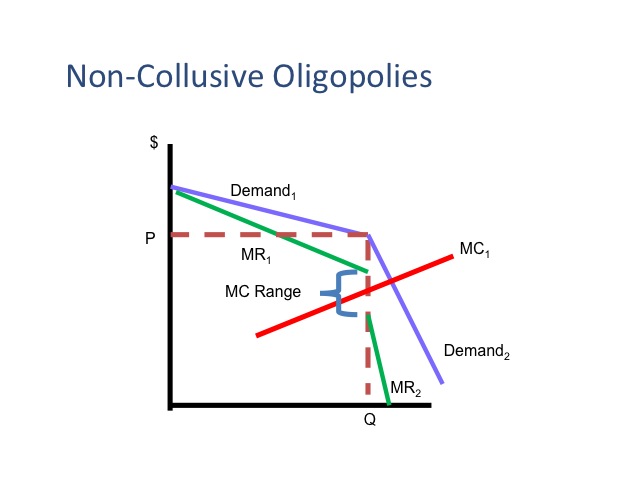

Since there are only a few firms in an oligopoly, their profits are interdependent. The kinked-demand theory explains the behavior of a firm in a non-colluding oligopoly. The assumption is that the firm faces two demand curves. If the firm were to raise its price, other firms would choose not to increase their price and would take a large portion of the market share away from the higher priced firm. Thus the demand curve, if the price is increased is very elastic, as shown on the left. If the firm decided to decrease its price, other firms would follow the price cut and decrease their price. Thus the demand would be relatively inelastic, as demonstrated in the graph on the right.

Combining these two demand curves yields a kinked-demand curve. If the firm raises prices, it faces the highly elastic demand (D1) and if it lowers price it will face a more inelastic demand curve (D2). Profit maximization still occurs where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, so the firm will produce quantity Q and charge price P. Note that given the disjoint marginal revenue curve, the marginal costs for the firm could increase or decrease a small amount (denoted by the MC Range) and the firm would continue to produce the same quantity and charge the same price. Thus prices are “sticky” at the original prices. How firms find the original price and quantity is a question asked by critics of the model.

One of the assumptions of an oligopoly is that there are substantial barriers to entry. If the barriers to entry were low, how would a firm behave? The contestable market theory argues that if the barriers to entry are low, oligopolies will behave more competitively with lower prices and greater quantity. This acts as a deterrent and discourages other firms from entering the market. In general for markets to be contestable, there must be relatively low start up costs (including sunk costs) for new entrants; the technology to produce the product must be available to new entrants, and there can’t be significant brand loyalty to the existing products in the market. In a contestable market, there may only be a few firms and yet they behave competitively due to the potential threat of new entrants. For example, although there may only be one or two gas stations in a small town, they may choose to keep their price of gas lower to deter other businesses from opening up.

Game Theory

Imagine you had been taken to New York with a friend and told that there are two other people in New York who are looking for you, but you don’t know who they are or what they look like. How would you go about finding them? Where would you go and at what time would you meet? This is an example of game theory--where you are trying to make the best choice based on what you think will be the actions of others.

This experiment was actually tried by ABC Primetime (March 16, 2006) with a group of people. If you would like, you may view the video using the link below. This video is about 40 minutes long, so it is optional viewing and not required. However, you may find it a very useful resource for understanding some of the basic ideas of game theory.

ABC Primetime (March 16, 2006) video on game theory

You can also read a transcript of this video at ABC News / Primetime: Mission Impossible: In Search of Strangers in New York City.

Since oligopolies are interdependent, game theory can be a useful tool in analyzing the strategic behavior of firms. Analyzing strategic behavior is useful in sports, politics, business, war, and even dating. In game theory, the payoff or reward to the firm depends on its actions as well as the actions of the others.

Think of the game of paper, rock, and scissors. What wins depends on what you choose and the choice of your competitor as demonstrated in the following article:

Listen To The Children by Lloyd de Vries (May 18, 2005)

A story about Christie's, Sotheby's, and more than $20 million worth of art. Takashi Hashiyama, president of a Japanese electronics firm, couldn't decide which auction house to use to unload the company's art collection. Did he ask them to enter a bidding war? Did he split the collection between the two auction houses? Did he ask around to find out which one had the fastest-talking auctioneer? No. He decided to use a decision-making process that kids have been using for generations: rock, paper, scissors.

Sotheby's decided to leave its decision to chance, and had no particular strategy. Christie's, on the other hand, turned to some experts: the children of their international director of the impressionist and modern art department. The 11-year-old twin daughters immediately told their dad to go with scissors. Their reasoning was that, "Rock is way too obvious, and scissors beats paper." So, Christie's chose scissors, Sotheby's chose paper, scissors "cut" paper and Christie's got the deal.

Source: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/05/18/opinion/garver/main696175.shtml

The media is full of examples of game theory. Watch the following clip from The Princess Bride:

The Princess Bride: Never go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line! (About 5 minutes)

GameTheory.net has additional examples of game theory in film.

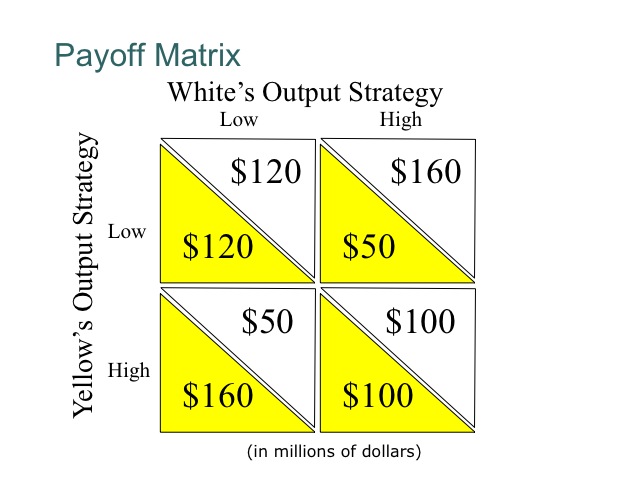

The basic components of a game include the rules, players, strategies, and payoffs. These need to be clearly defined in order to determine optimal strategies and outcomes. We can illustrate these components best though a simple demonstration of a simultaneous, on-shot, duopoly game. By definition, the rules of this game are that the players simultaneously choose their strategies (i.e. they cannot wait to see what the other will do). Once the strategies are revealed, the payoffs are determined and the game is over – no repeats or mulligans! The players in our game are two firms: Yellow and White. They each can choose one of two strategies: high output or low output. Finally, their payoffs are the profits they earn as a result of their strategy and that chosen by the rival.

A payoff matrix is a simplified representation that shows the possible payouts to each firm based each potential outcome. If both firms select the low output level (upper left-hand quadrant), each firm will make $120 million. If each firm opts for a high output level (lower right-hand quadrant) each will make $100 million. If White chooses a low output level and Yellow chooses a high output level (lower left-hand quadrant), White will make $50 million and Yellow will make $160 million. The reverse is true if Yellow chooses a low output level and White chooses a high output level (upper right-hand quadrant). Where payoffs are identical like this, we call them symmetric games. Since firms are choosing their output levels at the same time, they are unable to detect beforehand the decision of the other. In trying to anticipate the actions of the other, a firm evaluates the payoff matrix.

If Yellow chooses a low output level, White’s best choice would be a high output level since $160 million is greater than $120 million. If Yellow chooses a high output level, White’s best choice is again a high output level since $100 million is greater than $50 million. Thus regardless of Yellow’s decision, White’s best choice will be to produce a high quantity. This is known as a dominant strategy, since White’s best choice is a high level of output regardless of Yellow’s decision. Recognizing that White has a dominant strategy to choose a high output level, Yellow’s best choice is then choose a high output level since $100 million is greater than $50 million (you can also see that Yellow has a dominant strategy to choose a high output level due to the symmetric nature of the game). As a result, both firms will choose a high output level earning $100 million. Since neither firm can change its strategy to obtain a better payoff, given what its rival does, this is the rational outcome! When such an outcome is obtained, this situation is referred to as a Nash equilibrium. Now let’s be very clear, in this case White and Yellow both have dominant strategies and the Nash equilibrium is (high output, high output) with payoffs ($100M, $100M). Note, the Nash equilibrium is not the payoffs; it is the optimal strategies.

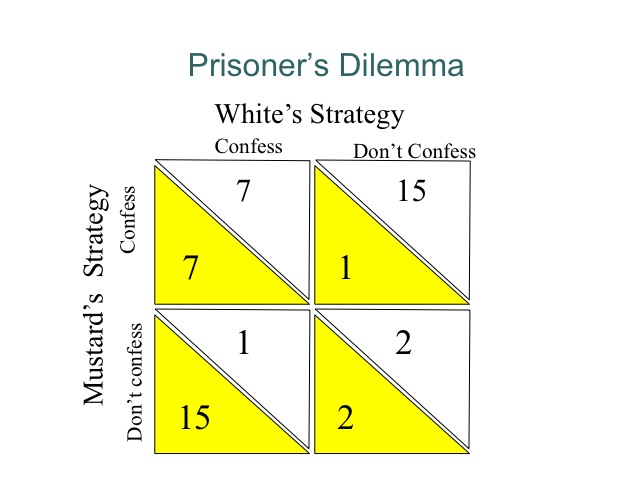

A common example used to game theory is the prisoner's dilemma. For example, say that Mrs. White and Colonel Mustard (using two characters from the board game Clue) are both accused of murder. They are apprehended and each placed in a different room and unable to communicate with each other. The above payoff matrix indicates the number of years, each will have to serve based on outcomes. If neither confesses, they will be charged with a lesser crime and each serve two years. If one confesses and agrees to testify against the other, he or she will only serve one year while the other will serve 15 years. If they both confess, they will each serve 7 years. Analyze the payoff matrix and determine the expected outcome.

This is a one time or non-repeated, simultaneous game. In analyzing the payoff matrix, we find that there is a dominant strategy and an incentive for both individuals to confess, even though they would collectively be better off by remaining silent. This simple example of the prisoner's dilemma demonstrates why the outcome will be worse for each individual than if they had cooperated and not confessed.

The structure of these games can be very complex or relatively simple. A simple game consists of perfect information with each individual knowing the payoffs and unable to cooperate or collude with the other party, a discrete set of choices, i.e., confess or don’t confess, and a single round.

In more complex repeated games, firms are able to punish those who fail to cooperate with strategies such as tit-for-tat, where one firm does what the other firm did in the previous round or the grim trigger, where a firm will seek to punish the other firm forever if there is any noncooperation. Asymmetric information, where information is known to one party but not to another, also makes the game more complex. In dynamic games, one firm is able to see the actions of the other then respond. Price match guarantees or 110% of the difference if another firm has a lower price discourages other firms from reducing their prices.

An important component in game theory is knowing that the payoff or penalty for an action is real. A child who misbehaves and is threatened by a parent with a particular punishment will find out if the parents threat is credible. A parent who fails to carry out an announced punishment, quickly losses credibility and often control of the child.

In war the threat must be credible even if the results can be dire. Go to http://www.gametheory.net/popular/film.html and watch the video clip of Dr. Strangelove. As demonstrated in this clip, the threat, in this case the use of nuclear weapons has to be credible and convincing and out of the control of “human meddling.”

In 2002, war between Pakistan and India was averted due to Pakistan’s threat to use nuclear weapons if India attacked with their conventional forces, which were superior to Pakistan’s conventional forces. “Pakistan does not abide by a no-first-use doctrine, as evidenced by President Pervez Musharraf's statements in May, 2002. Musharraf said that Pakistan did not want a conflict with India but that if it came to war between the nuclear-armed rivals, he would "respond with full might." These statements were interpreted to mean that if pressed by an overwhelming conventional attack from India, which has superior conventional forces, Pakistan might use its nuclear weapons.” Source: http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/pakistan/nuke/

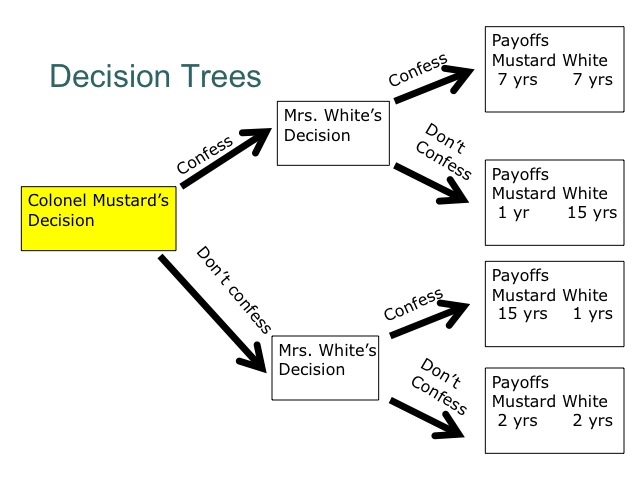

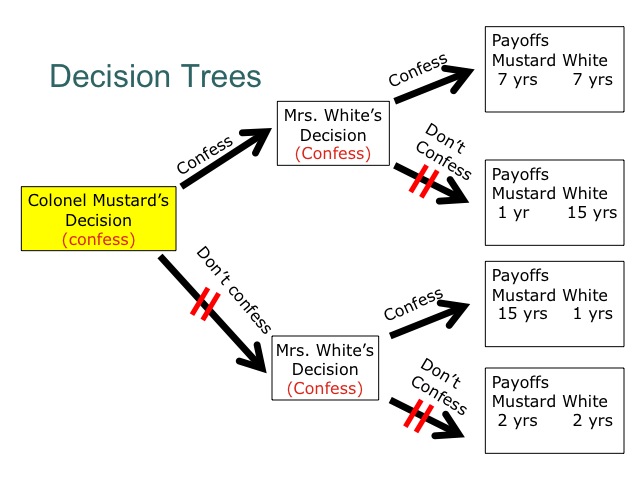

When games are sequential in nature, rather than simultaneous, we can represent them using decision trees. They’re also useful when analyzing more complex games. This tree can be used to consider the case of a sequential game when Colonel Mustard must make his choice first, and Mrs. White gets to know his decision before she determines hers. Notice that all the components are again included: the rules – sequential decisions and one shot game, the players – White & Mustard, the strategies – confess and not confess, and the payoffs – years in prison.

When solving the tree, we start at the right-hand side (or the end of the game) and work to the left (or back to the beginning). This is called backward induction. If Colonel Mustard confessed, Mrs. Whites best choice would be to confess, since 7 years of prison is less than 15 years. If Colonel Mustard does not confess, the best choice for Mrs. White is again to confess. Recognizing the rational choices of Mrs. White, Colonel Mustard need only consider the payoffs that remain (i.e. he can ignore those associated with Mrs. White not confessing). He therefore compares the payoffs of 7 years versus 15 years, and will opt to confess. The Nash equilibrium is (confess, confess) with payoffs of (7,7).

Sequential games like this help illustrate when there are first and second mover advantages. What do you think about this case? Does Colonel Mustard have a first mover advantage or does Mrs. White have a second mover advantage?

Game theory is an extremely powerful tool that can be used to analyze and predict the behavior of others when there are few parties involved and their payoffs are interdependent. It is particularly of interest when examining the behavior of oligopolies and their decisions to price, advertise, and produce.